“But that is how a tragedy like ours or King Lear breaks your heart—by making you believe that the ending might still be happy, until the very last minute.”

Oliver, If We Were Villains

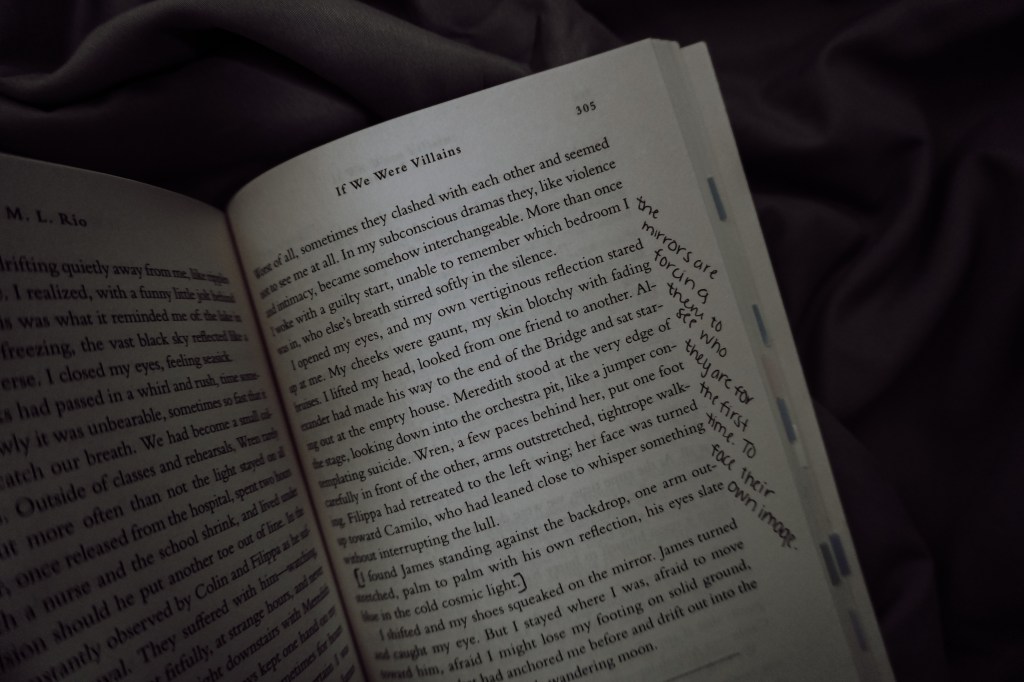

I needed a really good book after being so thrown off by the poor execution and writing of Cassandra Clare’s Chain of Thorns. It took me a while to even pick up another book because ChoT sent me into a bit of a slump, but I’m so glad I chose If We Were Villains to kick the reading blues away.

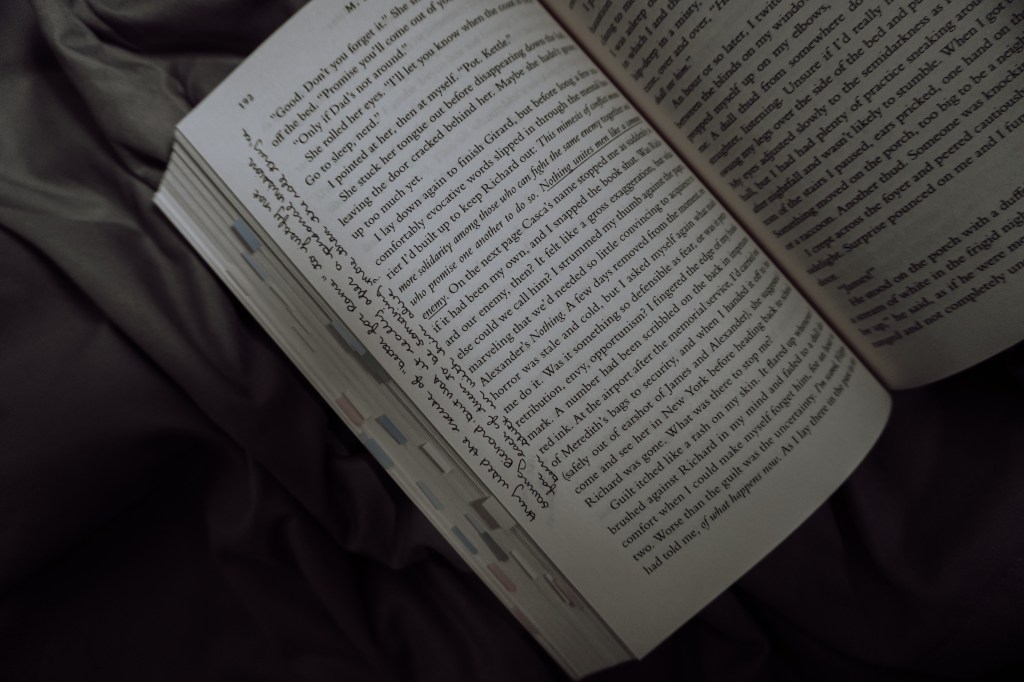

If We Were Villains by M.L. Rio is a dark academia thriller first published in April 2017 that follows seven thespian students studying William Shakespeare at Dellecher Classical Conservatory through the eyes of Oliver Marks as he recounts their fourth-year that ended in tragedy and his own conviction to the officer who put him behind bars a decade ago.

I absolutely loved this book. It hit so many of my personal favorites with strong literary references used as foreshadowing, that whimsically haunting academia vibe and strong themes. It was executed so well with unique structure and writing style, characters that are poetically and disastrously flawed, and a story that’s engaging and immersive for readers. However, if you’re not familiar with Shakespeare’s works, I think you might miss out on a lot of the nuances and the charm, and it’s pretentious — which is the point.

Here are all of my thoughts on If We Were Villains…

My non-spoilery review…

If We Were Villains is a tragedy with a narrator doomed by the narrative from the very beginning, but it doesn’t erase the unease or make the story any less tragic by knowing the genre. It’s a battle of fate versus free will, where freedom gravitates to divine destiny in true Shakespearean fashion. It’s exceptionally executed, using the five act play structure to immerse readers into the world of Dellecher and having William Shakespeare intertwined into the narrative so tightly he felt like a harbinger through his life’s works.

The story is divided between past and present to constantly carry tension as readers wait for the metaphorical other shoe to drop, and the writing itself is unique and haunting. The characters are not quite lovable but beautifully and realistically flawed in my favorite shade of morally gray as they force readers to ask themselves what they’d do for the sake of Rome — and is it truly just about Rome?

I would probably give this book five stars if it wasn’t so predictable. I initially liked the predictability personally, as a way to prove the point of tragedy. However, a part of me was hoping to be surprised by some turn of events. The ambiguous ending (which I adored) was close, but it wasn’t enough to completely throw me.

Still, If We Were Villains is a book you can sit with and chew over and turn around each line just like Shakespeare’s with an underlying message of the dangers of romanticizing academia and literature.

It’s going to be my go-to rec for a while, and I will definitely be reading this again because I feel like you can get so much more from it on a second read-through.

*** Spoilers Ahead ***

Fate vs. Free Will

One of Shakespeare’s most-used motifs is the pull between free will and fatalism — that’s because astrology was all the rage during the Elizabethan era. It was widely believed that people had a predetermined fate by God, that the stars and planets held power over man and that there was a hierarchy of creation that was delicate and couldn’t be unbalanced.

Those are ideas that were challenged and explored often by intellectuals, including Aristotle, whose theory that free will also played a part in the downfall of a tragic hero was applied to humanity as a whole by William Shakespeare in his works. Especially in his tragedies.

The three witches predict that Macbeth will be king, but Macbeth and his wife kill Duncan by their own free will. Julius Caesar was assassinated because of his own power hungry actions as a dictator. King Lear’s madness is because of his own decision to ignore the Fool. Romeo and Juliet die because they choose to.

Rio applies this same thinking to If We Were Villains.

From the very beginning, readers know Oliver was imprisoned. He’s destined to fall. However, even without the present-day prologues, Oliver’s character feels fated to take the fall from Act 1 Scene 1 where he thinks: “I seemed doomed to always play supporting roles in someone else’s story.” That quote is followed by James telling him, “Your time will come to be the tragic hero. Just wait for spring.”

This foreshadows Oliver’s fate of taking the blame for Richard’s death.

Not to mention that this coincides with the book starting with lines from Hamlet, particularly the gravedigger scene: “The gallows does well. But how does it well? It does well to those that do ill.”

That scene is used to foreshadow Hamlet’s fate and in turn Rio uses it to foretell Oliver’s.

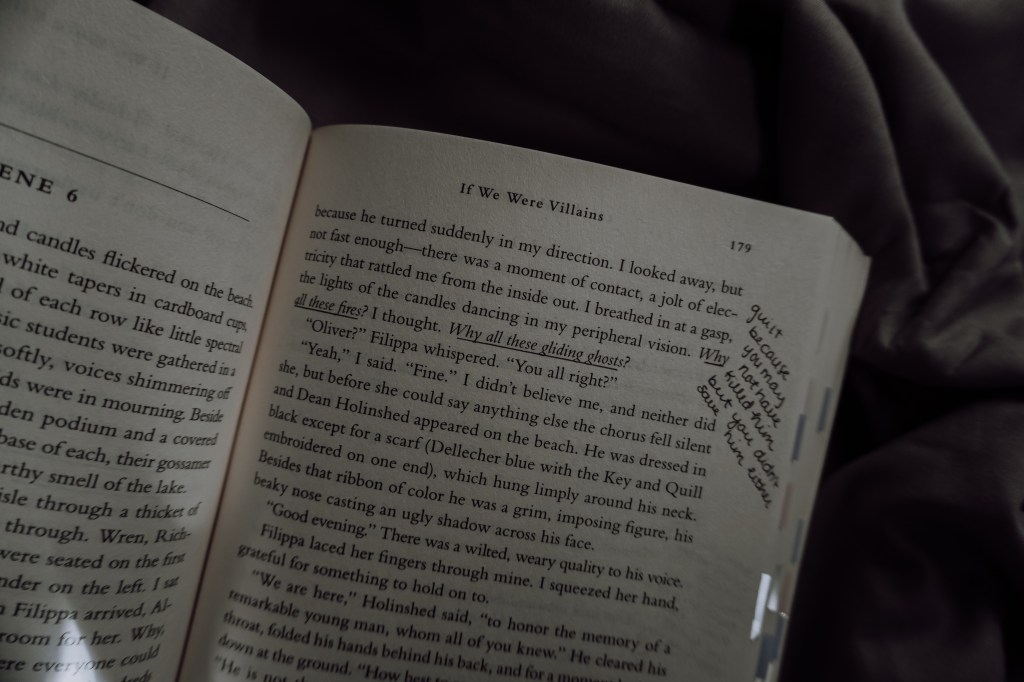

And much like Hamlet, our group of fourth-years — “Fourth year. The year of the tragedy.” — seem all-too aware of their fates. It portrays itself in the form of them accepting their roles as who they are meant to be both on and off the stage.

Our characters often relate themselves and their lives to Shakespeare’s plays, but the passage that stuck out to me most was when Frederick asked what a tragedy encompasses and each character delivered their own role in the story of their lives.

Richard the tragic villain (or the tyrant), James the tragic hero, Meredith the seductress with “conflict”, Wren the ingenue with “imagery”, Alexander another villain with “source material”, Filippa the chameleon with “structure” and Oliver the sidekick with “fate versus agency.”

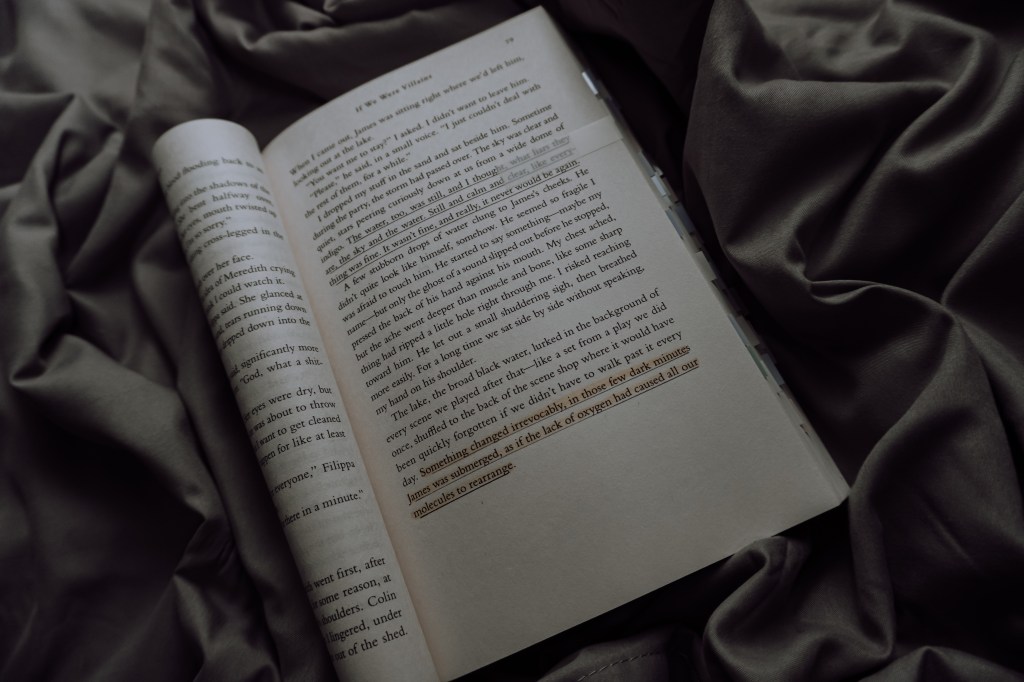

Side note! My favorite piece of foreshadowing in the book comes during this scene actually. They discuss the tragedy of Julius Caesar not being the political turmoil, but the betrayal. Caesar was murdered by a close friend, and that is the tragedy. This foreshadows James killing Richard and the moment he reaches out to his supposed friends as he’s dying as an act of betrayal by all of them, but also Oliver is the one who delivers this realization and thus foreshadows his own insertion into the tragedy.

Their group dynamic relies on that hierarchy of powers, and when it’s unbalanced with the Macbeth casting everything falls apart — just as fate would have it.

Richard, our tyrant, is killed by the hero James; Alexander, the villain, convinces the rest to let him die; our fragile little Wren was victimized by Richard; Fillipa blends into the background and is forgotten; and Oliver agrees to pull the body from the lake because he’s the one who makes everyone on the stage better and has been seduced by Meredith.

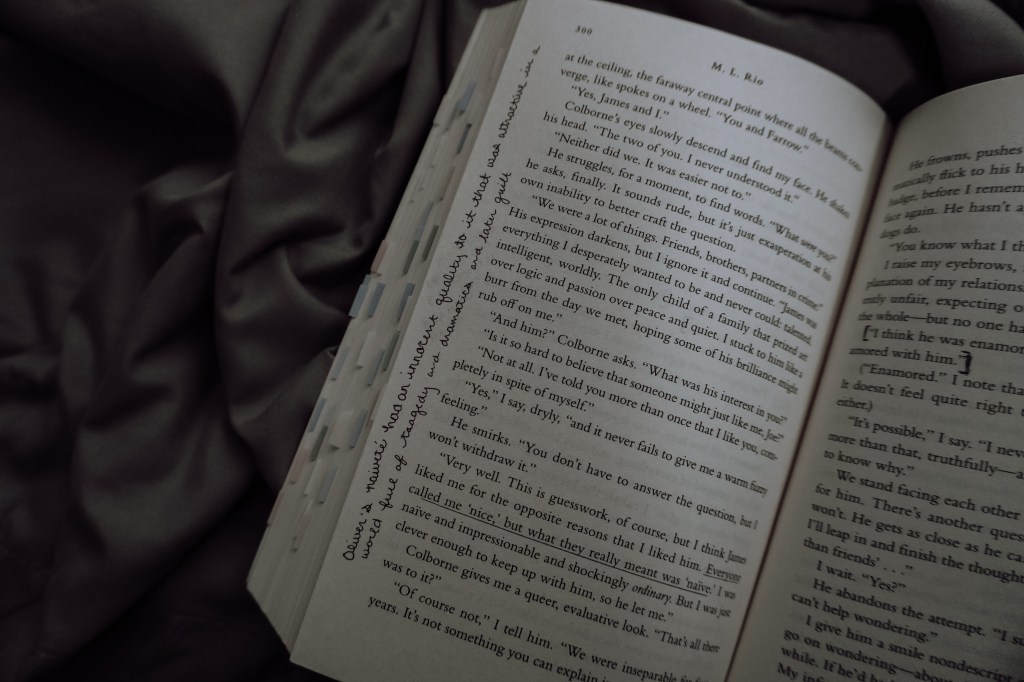

It’s this action of Oliver getting into the lake that plays into fate. He’s taking action toward a destiny that’s been foreshadowed without him knowing, because he’s an oblivious and naïve character. Everything after this moment is a series of fate and free will that coincide to lead Oliver to accepting what has been written in the stars.

He actually directly accepts it.

The night after they find Richard’s body, Meredith asks Oliver to go to bed with her because she didn’t want to sleep alone. He knows it’s a bad idea, but he thinks: “Our two souls — if not all six — were forfeit.”

And Oliver continues to have an undefined relationship with Meredith, despite James’ warnings and his own hesitations.

When he finds the scrap of cloth in the fireplace, he pockets it rather than handing it to Detective Colborne. He hides it and later the boat hook he found in James’ mattress.

Now those two specific things only happen because of situations outside of the frame of free will. Oliver has to clean because his parents couldn’t afford tuition due to his sister’s eating disorder treatment.

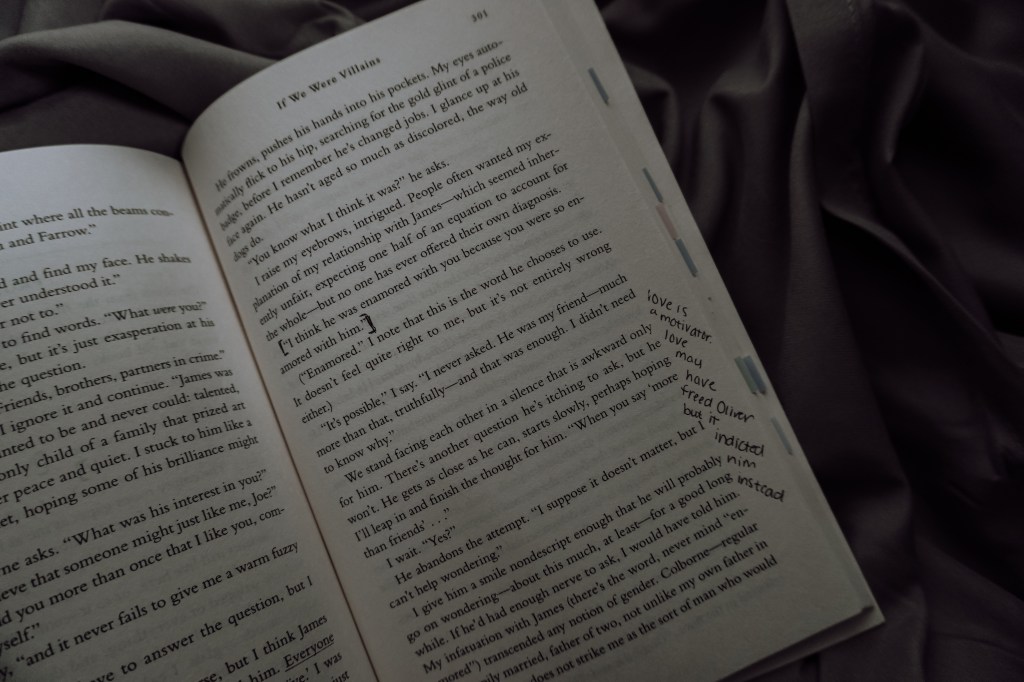

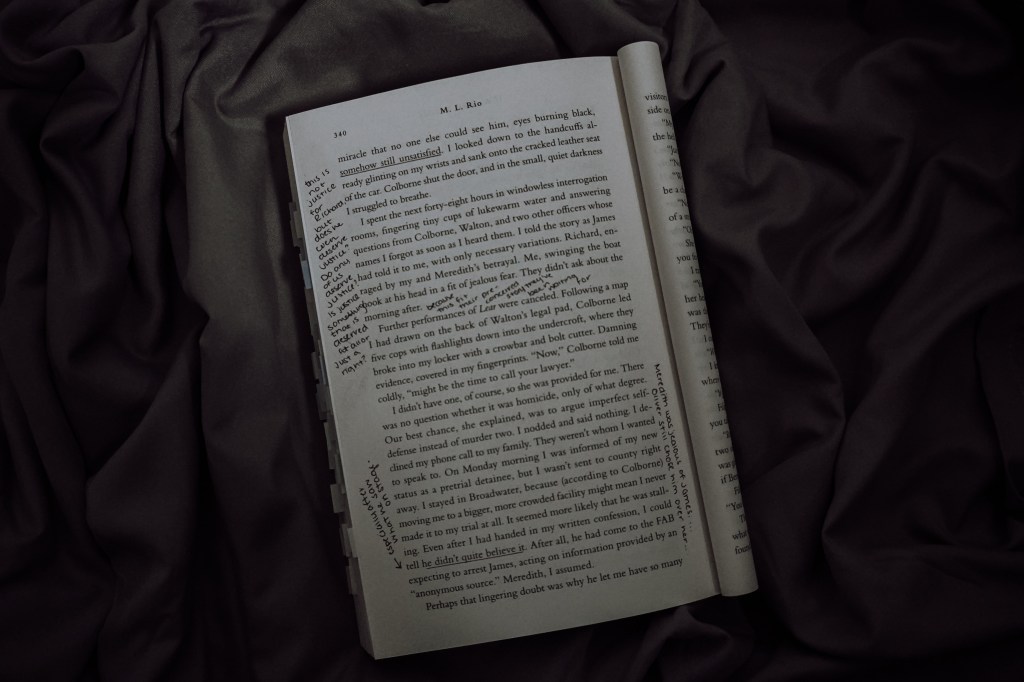

It’s what Oliver does when presented with these twists of fate that leads to his own downfall, because it can be argued that fate would want justice in seeing James be held accountable for Richard’s murder — that’s why Oliver sees him among the others as he’s led away in the cop car and he looked “somehow still unsatisfied.” Oliver helped defy fate for James, but in turn played into his own.

He makes the decision to take the fall for James on stage. A show of love to soften the tragedy — or maybe in his head, to avoid tragedy all together. Because he asks the others when they visit if they would change the ending of Romeo and Juliet if they could. However, would Benvolio taking the blame for killing Tybalt spare their lives? Killing Tybalt is one notch in the machine of that tragedy. Yes, Romeo is banished because of the murder, but he and Juliet would still be star-crossed lovers belonging to feuding houses.

And that plays out with Oliver and James. Oliver helps James avoid his own fate, and James still ends up dead (supposedly). We’ll talk about the ending later, but I have a firm belief that James wrote the letter for Oliver to keep his love alive through hope, because he knew the other man would think to end his own life as the conclusion to this tragedy.

And now that I’ve written this all down, I’m thinking … Oliver seems fated to take the fall because of early characterization and through his actions, but is he perhaps still just the sidekick that simply tried to help James thwart his own (not Shakespeare, but I was thinking Patroclus to Achilles)?

James predicted that Oliver would become the tragic hero in the spring, but he’s still the Benvolio to James’ Romeo.

“I seemed doomed to always play supporting roles in someone else’s story.”

Pointing fingers

The point of a mystery book is often to find who’s to blame for a crime or to figure out a puzzle. It’s about coming to a satisfying conclusion after hundreds of pages of putting together clues. But sometimes, there’s no one person or group to blame. Perhaps it’s about blaming fate, circumstance, the environment that allowed tragedy to unfold.

In If We Were Villains, James is to blame for Richard’s death. That’s if you look at it in a straight forward, black-and-white way. However, all six of the fourth-years decided not to save him when they saw he was still alive. Oliver even says himself that he convinced James when no one else could.

More than that, you could point fingers at Oliver for sleeping with Meredith that night. Or Richard for being an aggressive prick. Or Alexander for suggesting they let him die. Or Frederick and Gwendolyn for the casting. Or parents who failed to love and protect their children in all the ways they needed.

Or you can blame Shakespeare himself like Oliver does.

“Do you blame Shakespeare for any of it?”

“I blame him for all of it.”

Now Oliver isn’t exactly blaming Shakespeare as a person, he’s blaming the environment and lifestyle around this academic aesthetic that these Shakespearean thespians have created.

He goes on to explain the appeal of Shakespeare: “He speaks the unspeakable. He turns grief and triumph and rapture and rage into words, into something we can understand. He renders the whole mystery of humanity comprehensible.”

These seven young adults didn’t really have an identity of their own. They didn’t know who they were or how to explain the world, so they clung to the sense they found in Shakespeare’s works from whatever age they first found comfort in his words.

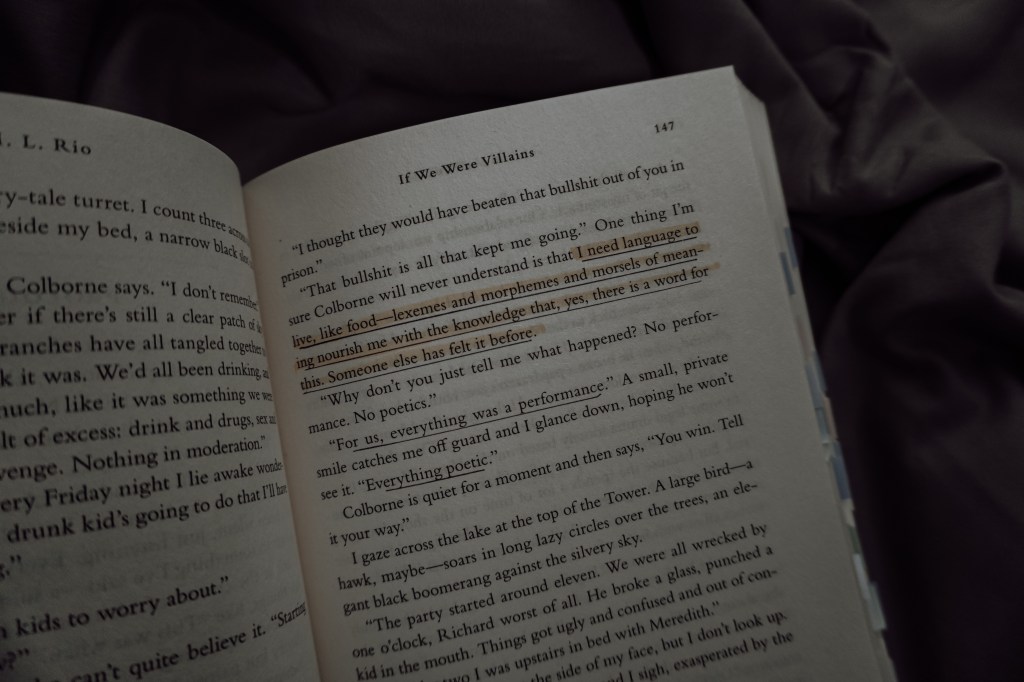

“I need language to live, like food — lexemes and morphemes and morsels of meaning nourish me with the knowledge that, yes, there is a word for this. Someone else has felt it before.”

At Dellecher, they found others like themselves, and found solace in that shared love and comfort of Shakespeare’s works to feel less alone.

“Here we could indulge our collective obsession. We spoke it as a second language, conversed in poetry, and lost touch with reality, a little. … Shakespeare is real, but his characters live in a world of real extremes. They swing from ecstasy to anguish, love to hate, wonder to terror. It’s not melodrama, though, they’re not exaggerating. Every moment is crucial.”

However, this did little to help their identity problem or lack of understanding of the real world. Instead, it created this echo chamber of beautiful words that only pulled away any little sense of self they had and replaced it with roles they became too comfortable with and then praised them for it.

“Dellecher was less an academic institution than a cult. … anything could be excused so long as it was offered at the altar of the Muses. Ritual madness, ecstasy, human sacrifice. Were we bewitched? Brainwashed? Perhaps.”

This college created a toxic environment for young people that were already a bit fucked up. Its competitive nature — which is shown simply through the fact that making it to fourth year is considered “surviving” —, its focus on art and beauty and performance, and its seclusion all allowed for these seven kids to drown in Shakespeare’s fiction and excuse their lack of awareness of real-life consequences.

“You can justify anything if you do it poetically enough.”

We see how poorly our group of main characters are at handling reality through some of the exercises they do in class — Oliver not moving and letting James hit him, the kiss between Meredith and James, the discussion about tragedies that turns to arguing, Richard hurting them all in practice and blaming it on passion, etc. When presented with conflict that’s more reflective of reality than fiction, they crumble.

While Oliver says he blames Shakespeare, I believe he’s really blaming the lifestyle they fell victim to at Dellecher. He says it outright in Act 1 Scene 1: “We were always surrounded by books and words and poetry, all the fierce passions of the world bound in leather and vellum. (I blame this in part for what happened.)”

From there, Rio does a really good job at proving that it is partially to blame through Oliver’s POV by immersing readers in that world — first with all the Shakespeare references and by the overall view of Dellecher before, during and after the tragedy unfolds. Oliver still has such a fondness for the campus and environment.

“There are things they don’t tell you about such magical places — that they’re as dangerous as they are beautiful.”

There was also a moment where he said he could still picture the seven of them running through the woods during third year — the year of the comedy — and there was an air of nostalgia that so little had changed in the decade he’d been behind bars.

His life had changed. All of their lives had changed so drastically, and yet the campus remained so eerily similar as if Oliver took the blame for it, as well.

And maybe he did.

But Dellecher isn’t solely to blame. Just like not one person can be blamed. It’s a shared guilt.

Fillipa tells Oliver in a present-day prologue that Alexander will be leaving his acting company because he refuses to do Julius Caesar since he blames that play for what went down, and Oliver asks, “You think it was Macbeth that fucked us up?” To which she responds, “No. I think we were all fucked up from the start.”

Fillipa doesn’t blame Shakespeare or Dellecher — she’s working there now, so she’s not removed from the environment — but the circumstances of their lives.

We know these young adults had less-than-ideal childhoods in different ways — neglect, hubris, absent, etc. Readers don’t get the full picture on each character, but that’s because there’s not a lot of emphasis on it. They aren’t the person they were before Dellecher, they are their roles; but also we only know what Oliver gives us, and he doesn’t believe this thinking.

However, based on what we do see, it seems clear that their upbringings played a part in them finding sanctuary at Dellecher and finding comfort in that environment.

Oliver’s home life is tumultuous. His parents don’t take his passions seriously. He’s not as much of a priority as his sisters. Meredith has money but not love or support or even her family’s presence. Wren and Richard felt sheltered. Alexander had an unstable life in foster care, and James had parents who simply didn’t care as much about him as they did about poetry. Nobody really knows anything about Fillipa at all.

Dellecher gave them stability and family.

I suppose everything leads back to Dellecher.

Or maybe it was all just written in the stars to happen and there was nothing our characters could do to prevent it.

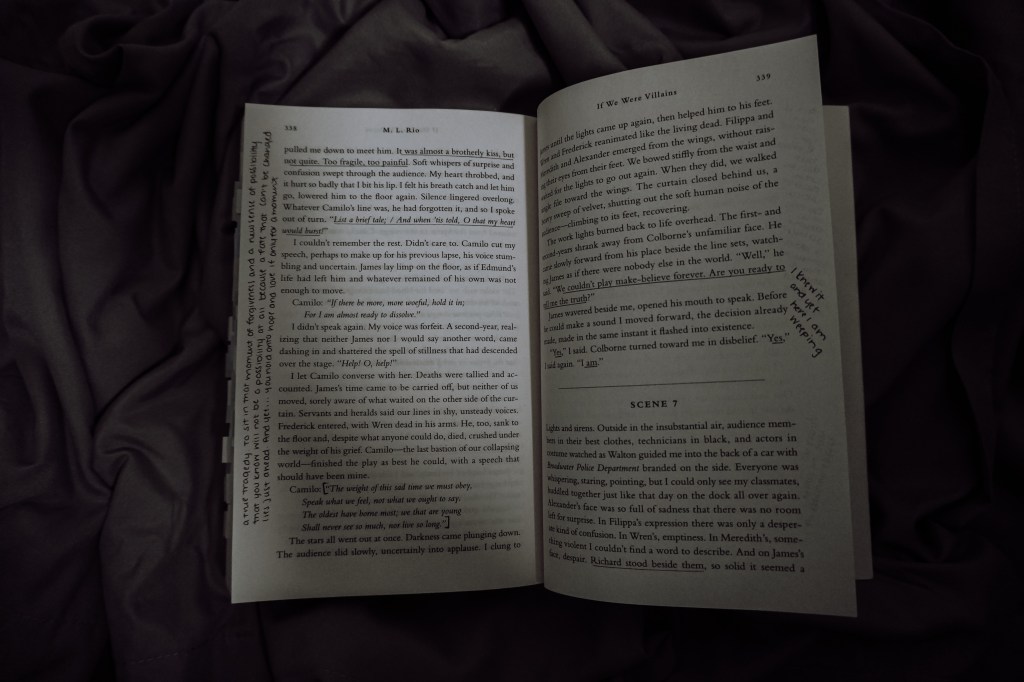

James delivers the book’s namesake line from Edmund’s soliloquy in King Lear right before Oliver admits to murdering Richard for him.

“…as if we were villains on necessity; fools by heavenly compulsion.”

It’s so clever to have James as Edmund, since Edmund is a unique Shakespeare villain. He works very selfishly by defying society, laws and morality, but also doesn’t have ill intent and has clear motivations.

Edmund acknowledges that humanity is responsible for their own actions, and that we want to blame the stars for them in a way to free us of guilt. But also he’s pointing out the foolishness of his father for counting on the stars to excuse everything.

I like to think James delivering this line is him preparing to accept what he’s done. It was not fate that led him to kill Richard, it was fear and rage and self-preservation … maybe even love … that drove him to commit this crime.

However, Oliver takes that away from him by taking the blame for himself.

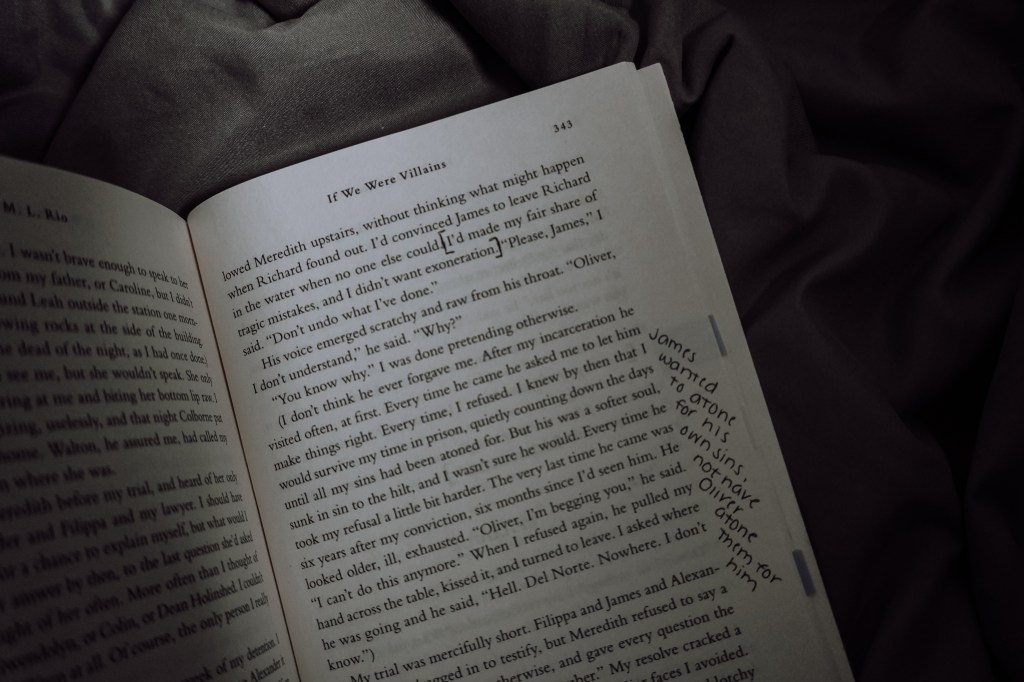

And in that, Oliver tries to atone for sins that aren’t entirely his own … and James has to simmer with his actual sins.

So … that ending …

I am such a fucking slut for an ambiguous ending, and it made so much sense for If We Were Villains to end on such a big ‘what if’. This was not meant to be a satisfying story — much like any tragedy — and this sealed the deal.

So Oliver is told that James drowned himself out of guilt; however, he left a letter for him which is a series of lines from Pericles.

I’m going to be honest. Pericles is the Shakespeare play I probably know the least about. I never studied it in full in any of my schooling, so I had to brush up on the story.

I think the biggest takeaway is that twice in that play Pericles believes someone he loves is dead — his wife and his daughter — but then he finds them alive. They’re reunited as a family at the end after a series of trials and tribulations.

At first glance, it’s easy to think that leaving these lines is a hint to Oliver that James isn’t dead. Pericles is referenced only by James and Oliver throughout the novel, while the other plays are shared amongst the group. James recited lines on the beach when Oliver visited him in California, and Oliver uses it to audition at the beginning of the book.

It feels symbolic of their relationship, or at least can be used in that way, as Oliver thinks he has won a trial for the sake of a happy ending and James is asking for help to be saved.

“A man throng’d up with cold: my veins are chill, And have no more of life than may suffice To give my tongue that heat to ask your help; Which if you shall refuse, when I am dead, For that I am a man, pray see me buried.”

These lines combined with the fact James’ body was never found offers hope that he’s not dead and that this tragedy may have a happy ending after all. There’s also the detail that the last time James saw Oliver, he said he didn’t know where he’d go and listed a bunch of places … including Del Norte, which is where Oliver recounts the last time he heard the above line when James uttered them as they lay on the beach.

However, I sat with this a while, and I think James is dead but left hope to keep Oliver alive in two possible ways.

He would know that Oliver would possibly also commit suicide in true Romeo and Juliet fashion to complete the tragedy.

Both Richard and James are paralleled to the sparrow in Hamlet, so I think this Pericles passage is meant to say that in death, James has flown to a guilt-free place to exonerate himself while abiding by Oliver’s wishes. He wouldn’t want Oliver to live with the same guilt he did, so he writes these lines as a message of hope that they’ll find each other again in this place.

But there’s still the fact James’ body was never found. Perhaps he staged his death in one place and followed through with the act in Del Norte. … “pray see me buried” … Maybe James gives Oliver a hint as to where to find his body so that he can have more intimate closure.

James truly being dead fits his character, and it fits the tone of Shakespearean tragedy.

However, I think the ending can be whatever you’re looking for in this book — hope, happy endings, tragedy. It’s like what Oliver says, “I am all too aware of my own desperate need to find a message in the madness.”

Is any of this true?

Less analysis and more just musings on this one …

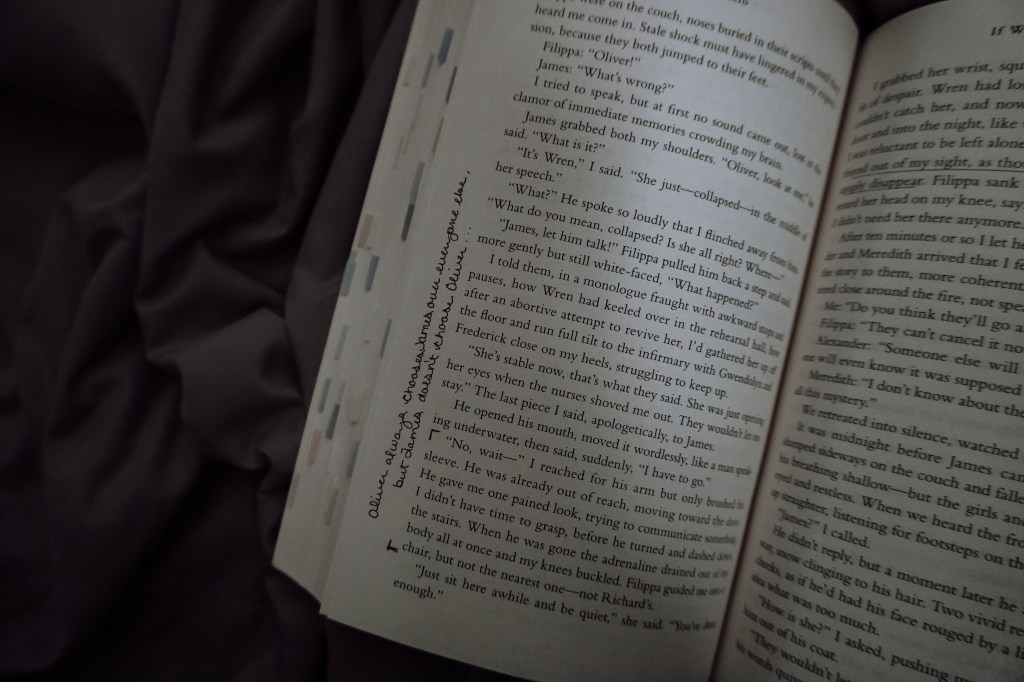

If you’ve been around here awhile, you know I love an unreliable narrator. Oliver is 100 percent an unreliable narrator, and it adds this incredible level of curiosity to this novel. It’s even toyed with throughout the book. Oliver is a trained actor. They all were. “We are arrant knaves, all. Believe none of us.”

But more than that, Oliver is just a very oblivious character. He didn’t even question seeing James in the bathroom. He’s not very observant or challenging. He just sort of takes everything for what it is — like James and Wren or Meredith with him.

Nothing Oliver says can be trusted.

I love it.

I love that you just have to accept it. Much like Colborne does — which is a really cool way in itself to allow the unreliability to not be satisfying but acceptable by experiencing it alongside the detective. We as readers can relate to Colborne’s curiosity and mistrust.

It kind of reminded me a bit of the ending of Life of Pi. You can choose to believe whichever story you’d like. Whichever path helps you sleep at night.

Do I believe that Oliver is telling the truth?

Partially.

I think he’s a better actor than he lets on — it fits his characterization. There’s a chance he skewed the details to give Colborne a story that fit his initial thinking while staying loyal to his friends.

But also, I don’t think James gave Oliver the whole story to begin with. He said it himself that he didn’t want Oliver to look at him the way he did, so it would make sense if he sugarcoated the story to soften the look. Also wouldn’t it hurt so much worse if it wasn’t simply accidental murder on the account of self defense and Oliver took the blame? Or was it a secret James took to the grave? Was that the guilt that ate James alive? Did James maybe tell Oliver that during one of their visits and that is what he left out of his story to Colborne?

I’m not sure, but Oliver does say, “I have nothing of my own now, not even secrets.”

Is that acting or a genuine musing?

Who knows.

I love that ambiguity.

Rating

4.8 eerie lakes out of 5

Leave a reply to Bry Cancel reply