“Dorian Gray had been poisoned by a book.”

Yes, Dorian Gray was poisoned by the yellow book gifted to him by Lord Henry, and I feel as if I was poisoned by a book I picked up entirely on my volition.

There are books we come across throughout our lifetime that define who we are as people. They take pieces of our heart and mold themselves into our soul. For me, it was Rick Riordan’s The Lightning Thief in middle school, To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee junior year of high school, and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes throughout college.

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde is the latest addition to my list.

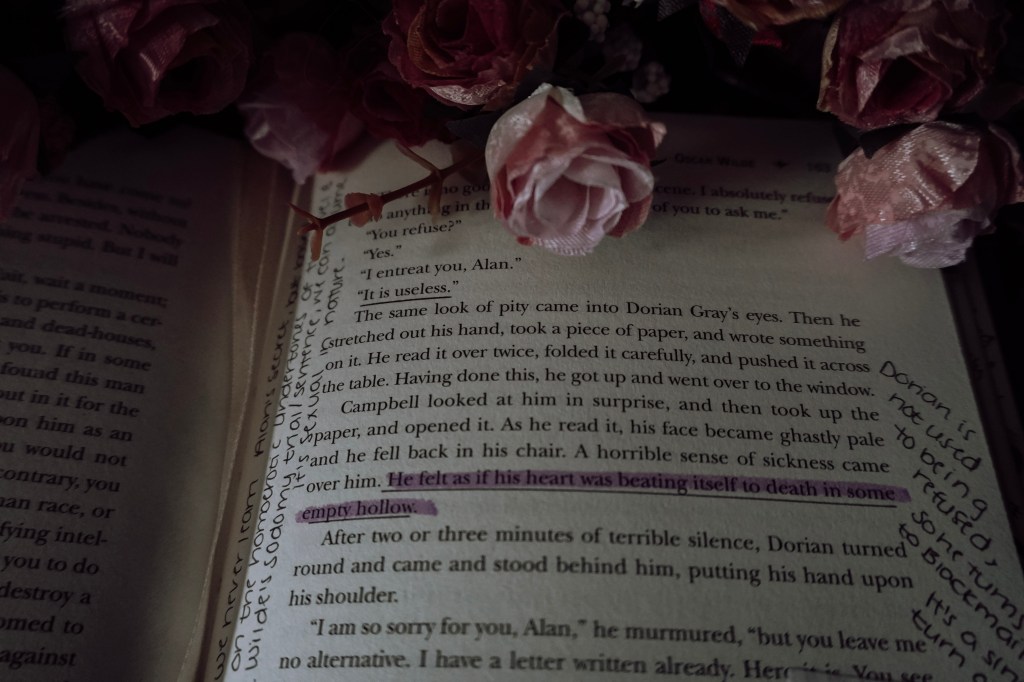

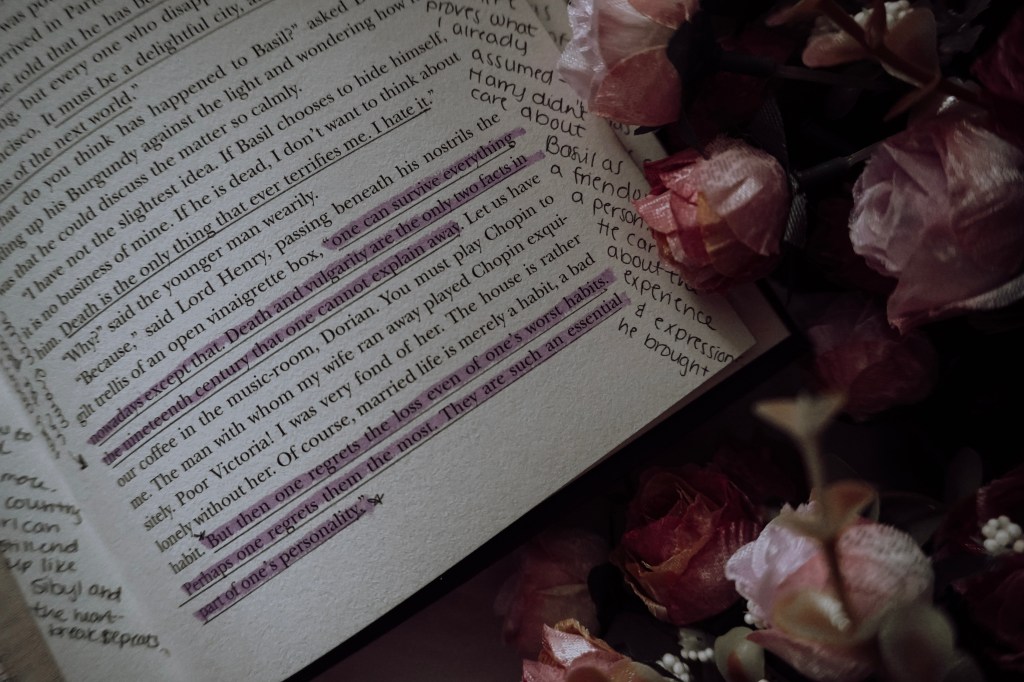

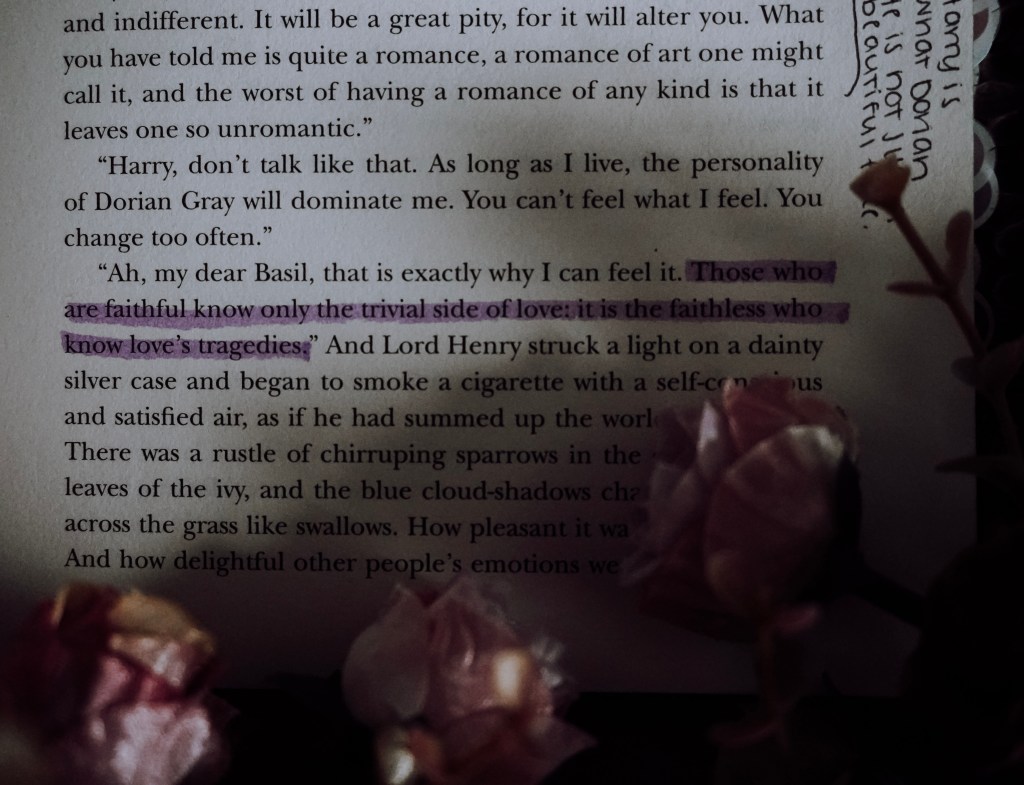

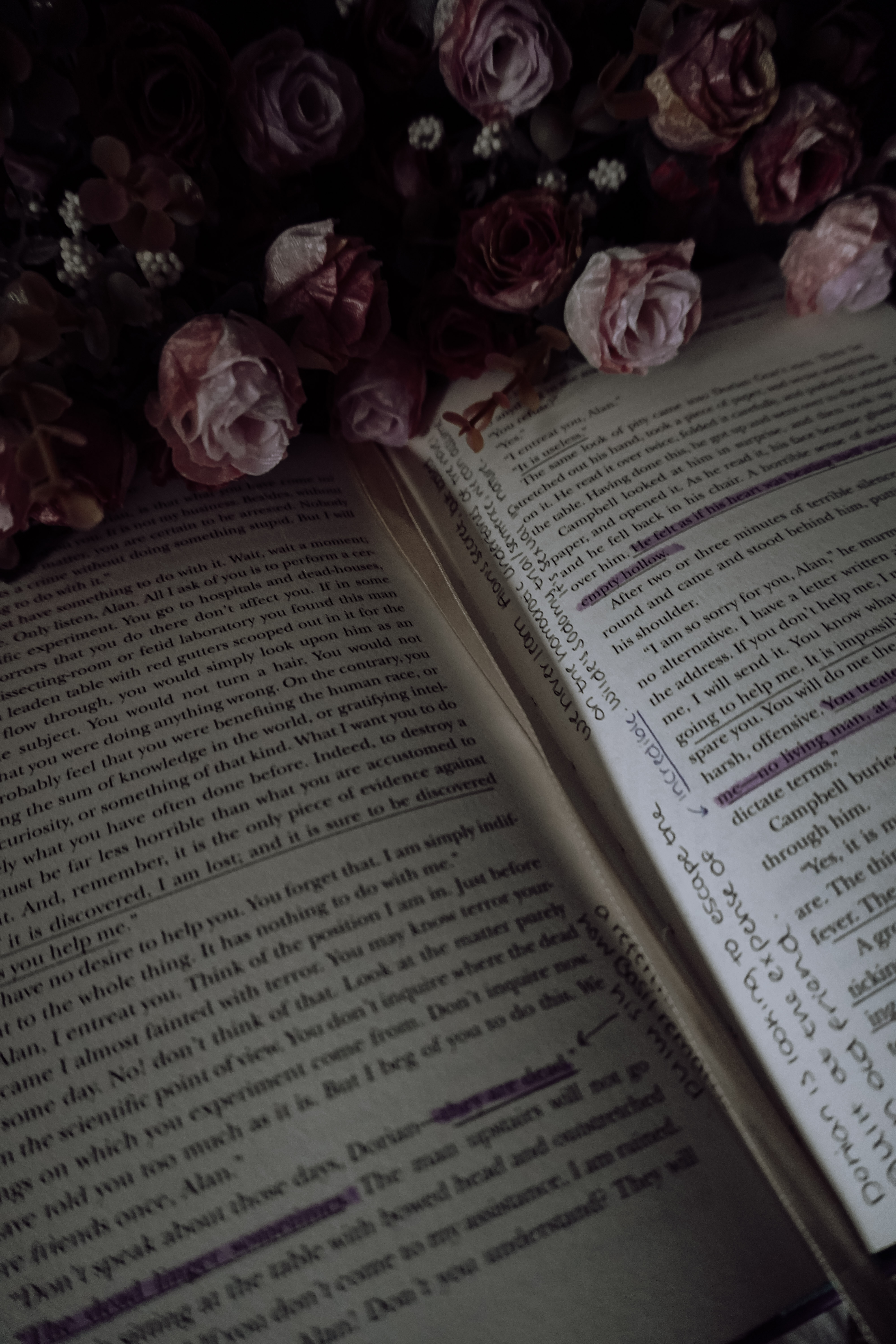

I feel as if I gave up a piece of my soul when I finally closed this novel — folded it and placed it within the pages among my endless scribbled annotations that filled the margins to the brim.

Dorian is a beautifully tragic piece of literature that holds up a mirror to society and how we view art and humanity. It’s a tale of ruination that you simply can’t look away from.

With that being said, this analysis will be a little bit different than my usual ones. This will be less structured and more of a stream of consciousness. Just an advanced warning for the chaos of me pouring my heart out.

A little bit about The Picture of Dorian Gray

If you haven’t read TPoDG before, it’s the only published novel by Wilde and first appeared as a shorter, heavily edited novella in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine on June 20, 1890. The full-length novel was published in April 1891 by Ward, Lock and Company.

It follows a young, naive Dorian Gray in Victorian London as he falls into a life of corruption after pledging he would give anything to stay as youthful and beautiful as the portrait painted of him by Basil Hallward. As Dorian ignorantly dives deeper into the pursuit of pleasure and art, the portrait hidden in the attic deteriorates while he remains unchanged physically. However, the weight of his sins on the painting continuously haunt him.

Heading into this novel, I knew more about Wilde than about this book. I honestly didn’t even know it fit into the gothic horror genre. Yes, burn me at the stake. However, I did know that this novel was used as evidence against Wilde in his sodomy trials in 1895 — five years after publishing Dorian Gray. That knowledge makes this particular line by Basil hit a lot harder:

“The reason I will not exhibit this picture is that I am afraid that I have shown in it the secret of my own soul.”

Also, a fun fact is that Wilde agreed to write the story for Lippincott at a dinner with a publisher and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. It was at this dinner that Doyle also agreed to write a second Sherlock Holmes story. The detective very well could have been a one-hit wonder if it weren’t for this meeting, and it’s often referred to as the most important dinner in literature.

I have a lot of useless information on the relationship between Bram Stoker, Doyle and Wilde, as well; however, I will save that for another time. The important thing to note is that Wilde bled his soul onto the pages of Dorian Gray, and it helped lead to his indictment. It changed the publishing industry as authors had to censor themselves out of fear their works could be used against them.

A really good example of this is in Stoker’s Dracula. In the originally published British editions, Dracula says to the three weird sisters, “To-morrow night, to-morrow night is yours.” In the 1899 American edition, this was added:“To-night is mine.”

The addition in the American version implies that Dracula planned to feed on Jonathan that night, which would’ve been seen as scandalous in England only two years removed from Wilde’s trial — Stoker actually began writing Dracula a few months after his frenemy’s trial. However, the Americans would be much more relaxed with the idea of a man feeding off the blood of another man.

OK, that’s all I’m going to get into with context … for now. Maybe I’ll make a whole post about this trio at another time. Until then, let’s talk about The Picture of Dorian Gray as an actual novel.

My thoughts

First and foremost, Wilde hits readers with one of the most prolific prefaces I’ve ever read. He delivers this wonderful line: “There is no such thing as a moral or immoral book.”

It sets the tone for the novel before it even begins. Art is simply art until you, the perceiver, put meaning to it. It’s a philosophical question that pertains directly to Wilde. He was a gay man in a time and place that persecuted you for love. Anything he wrote would be considered immoral by society, not because of its contents but because of who he was. To me, in the context of time, it felt like a challenge to the reader by its author to really take in each and every word and decide for yourself what they mean — or if they mean anything at all.

I believe in this simply because of what Dorian Gray presents, and that’s a satirical mirror being held up to the society in which Wilde lived and was condemned by. You believe a book to be immoral, because you are too afraid to look into the mirror and see your own sins plastered on your face or too fearful to look outside of societal standards. Through fear, you project immorality onto art.

I think of this quote by Dorian to Lord Henry: “You will always be fond of me. I represent to you all the sins you never had the courage to commit.”

The book does the same thing to its readers, especially at the time of publication, and it becomes a beautiful paradox from the get-go.

When we talk about setting the tone for this novel, I would also like to hit on my absolute adoration for Dorian as a character.

I love my fictional friends to be a beautiful shade of morally gray, and Dorian is my favorite hue.

He is young, naive, handsome and good. At least he was good. Wilde sets up this purity of Dorian in exquisite fashion. First, with Basil’s god-like description of the boy to Lord Henry and later by showing readers Dorian’s purity with his playing piano and feeling guilty for forgetting a show he was meant to play in Whitechapel.

Wilde paints Dorian as this perfect image of innocence, but it derives from ignorance. By ignorance, I mean that Dorian is unaware that he sits in a place of privilege due to his beauty, youth and wealth; which can all be very fleeting. Of course, everyone has to come to terms with their own mortality and the loss of youth, but you can either take it in stride for what it has taught you, or do as Dorian does and become desperately obsessed with never losing it.

Knowing the Dorian at the beginning of the book makes the downfall so much more impactful and harder to read. It’s the perfect character timeline with this setup, the journey to the top of the mountain being Dorian’s jump from one pleasure to another, the climax being Basil’s murder and then the descent into madness to forget the deterioration being the ride down to our main character’s own death.

Honestly, I think Dorian should be used as an example of the perfect character arc in every literature and writing class.

Going along with Dorian’s character development, one of the major themes of this novel is the power of influence.

It appears that every step of the way, influence is the real villain of this story.

It’s the unconscious influence Dorian holds over Basil that leads to the portrait being painted so passionately in the first place, but it’s Harry’s influence that puts meaning behind the picture.

Harry tells Dorian: “When your youth goes, your beauty will go with it, and then you will suddenly discover that there are no triumphs left for you … Live! Live the wonderful life that is in you! Let nothing be lost upon you. Be always searching for new sensations. Be afraid of nothing.”

This is what leads to Dorian making the wish, “If it were I who was to be always young, and the picture that was to grow old! For that — for that — I would give everything!”

Harry plants the seed within Dorian. He pushes his philosophies of hedonism and aestheticism, but society also rewards Dorian in a way for embracing them — or, at least, it doesn’t hold him accountable because of the weight it puts on class, wealth and beauty.

Influence is scattered throughout the novel. We see Sibyl Vane’s influence on Dorian as she holds him on a righteous path, then Dorian’s own influence over her is more obsessive — similar to the idolic view Basil has of the younger man. Sibyl loses herself and her passions because she is so overwhelmed by the affection of Dorian’s influence, which leads to her suicide.

Readers are also treated to a series of off-page influence. As Dorian falls further into sin, it’s told that he affects everyone in the same way he captured Sibyl and how he was taken by Harry. His influence scars everyone he becomes close to in a way he can’t be, because he has the safety net of the portrait.

This ominous influence is one of my favorite parts of the novel. I love not knowing what exactly Dorian has done to these close friends who become enemies and victims. It allows the reader to decide for themselves which path of corruption Dorian led them down. We get to draw the line between morality and immorality.

The portrait itself also has influence over Dorian. His fascination with its ruination drives him to live more decadently to see its degradation. No matter where he goes or what pleasure he finds, he’s tethered physically and mentally by the portrait and what it means.

It’s the portrait’s existence that brings him to kill Basil and later kill himself in an effort to cleanse his soul.

However, for as powerful as influence is, Dorian still holds responsibility for his actions. Multiple times he reflects on the influence Harry and the yellow book have over him and wishes to be rid of it, but he always turns back into the abyss until it closes around him. He wishes to blame everyone but himself for what has been done to his soul; however, it is his own draw to pleasure and what it gives him that leads him astray. He is at fault as much as anybody else, and I think that the ending really drives home that, at the end of everything, he must be the one to face the consequences of what he’s done to himself and those around him. It’s poetic justice in a very dark and twisted way.

The power of influence is paired with themes of art, beauty, youth and societal standards. These are all powerful together and on their own, but what stood out most to me was actually the symbols and motifs used to convey them.

Specifically, I was obsessed with the use of the color white to symbolize purity and innocence and how it’s consistently used throughout the novel to juxtapose Dorian’s unclean portrait.

In Chapter 3, upon learning Dorian’s parentage, Harry says, “Grace was his, and the white purity of boyhood, and beauty such as old Greek marbles kept for us.”

White in this instance is marking Dorian as a blank slate. He is clean, pure and innocent; and Harry sees it as a challenge to “dominate” the young boy. He wishes to paint his own portrait of Dorian on the boy himself.

Dorian also often has white orchids delivered, but he avoids them as the novel progresses. That may be because he often describes Sibyl as a white flower — “She trembled all over, and shook like a white narcissus,” and, “The curves of her throat were like the curves of a white lily.”

After Sibyl’s death, Basil is horrified that Dorian went to the Opera and says, “Why, man, there are horrors in store for that little white body of hers!”

Like with Dorian at the beginning of the novel, white is repeatedly used to show the innocence of Sibyl.

This is put into stark contrast against the portrait to the point Wilde even writes a scene of Dorian looking at the difference between his unchanged hand and the painting.

“He would place his white hands beside the coarse bloated hands of the picture, and smile. He mocked the misshapen body and the failing limbs.”

It’s a physical manifestation of Dorian’s loss of innocence in such a disastrously beautiful way.

It’s brought up again in the moments before Basil’s murder, when the artist delivers this biblical verse from the Book of Isaiah: “Though your sins be as scarlet, yet I will make them as white as snow.”

Basil wishes to figuratively clean Dorian’s hands, to make them white again instead of red after decades of sin have stained them. However, Dorian doesn’t wish to take the blame for what he has become and instead kills Basil in an attempt to rid himself of who he believes is the perpetrator.

Once again, the color white is used in describing Basil’s body: “How horribly white the long hands looked.” Basil was an innocent man. A man who simply painted a lovely portrait. It’s fantastic in reflecting that this murder will not help our main character’s predicament, but add to his ailments.

Later on, Henry’s fingers are also described as white, which shows he is also still innocent despite his influence. He is not the one committing the acts. Hetty Merton’s ‘white face’ also peers out from a window toward the end of the novel, which points to her own innocence that has perhaps been preserved by Dorian.

However, with Basil, Sibyl and James Vane, white seemingly becomes associated more with death than purity/innocence. Perhaps that is why Dorian, in his final moments, longs for “the unstained purity of his boyhood,—his rose-white boyhood, as Lord Henry had once called it.” He wants not just his innocence back, but the wind of life to be breathed back into him.

We love a good motif around here.

One more major symbol that I loved was the opium den being a physical reflection of Dorian’s ruination. He runs to the den to forget — who he is and what he’s done and the portrait rotting away in his attic — yet he’s greeted by a room full of people who are identical to him.

“He wanted to be where no one would know who he was. He wanted to escape from himself.”

All of these people — these “grotesque things” as Dorian calls them — were artful and beautiful in some way, but had dragged their souls through the mud in the search for decadence and in the compulsion of sin until all they could do was drug themselves into forgetting the reality they’re haunted by.

They do not have the eternal physical beauty as Dorian does to protect them from societal downfalls, and they become trapped in the hole of forgetfulness because they have nowhere else they can go.

Perhaps the real horror of the novel is knowing Dorian is not alone in his deterioration. It is an epidemic among humanity.

Side note: Basil delivers one of the absolute best love confessions I’ve ever read. “The world is changed because you are made of ivory and gold. The curves of your lips rewrite history.” Excuse me, Oscar, but did you really write this and then not expect the bigot police to pull up?

Final Review

The Picture of Dorian Gray will sit with me for the rest of my life.

I loved Wilde’s poetic writing, his humor and his soul that was bled on every single page. You can tell so much of his own heart was poured into this story.

Dorian’s descent into ruination was crushing. The jump from one decadent sin to the next in the pursuit of pleasure that leaves him forever unsatisfied was frustrating and devastating to read. I wanted to love Dorian. I did love Dorian. I rooted for him to be better, to push away the influence of Lord Henry and live for himself. To find beauty in life at its purest and not by burying himself so deeply in art that he no longer knew where the line was between it and reality.

The way the portrait consumed Dorian to the point of madness was unsettling and haunting — the perfect tone for gothic horror — and the themes of this text are unmatched by any other piece of classic literature I have read prior. It was meant to hold a mirror up to the high society of the Victorian-era, but can do the same for the 21st century. It presents the philosophical question of morality in a twisted and enthralling way.

I found myself gasping in shock at a book written 130-plus years ago. I knew the story, but I also didn’t at all. It captured me in a way so few books have in my life. If I ever plan to reread, which I definitely will, I’ll need to buy another copy. My margins are nearly full after one read through.

Dorian Gray is a perfect five rotting portraits in the attic out of five.

Leave a comment