Analyzing my reread of the first book of the Percy Jackson and the Olympians series

I broke my New Year’s Resolution.

At the start of 2022, I promised myself that I would not succumb to the overpowering urge to reread any books. Well, I lasted four months.

The announcement of Walker Scobell, Aryan Simhadri and Leah Sava Jeffries as the main trio in the upcoming Percy Jackson and the Olympians TV show made me absolutely weak. I just had to reread The Lightning Thief. I had to.

Plus, I could feel myself sinking into a reading slump. (I’m way behind on my goal for the year.) While I loved the Six of Crows duology, it mentally exhausted me. I needed a good comfort book that I could breeze through without much thought.

The only problem is … well … as yinz all know … I can’t just breeze through a book without much thought. I have to give ALL MY THOUGHTS. *cue laugh track*

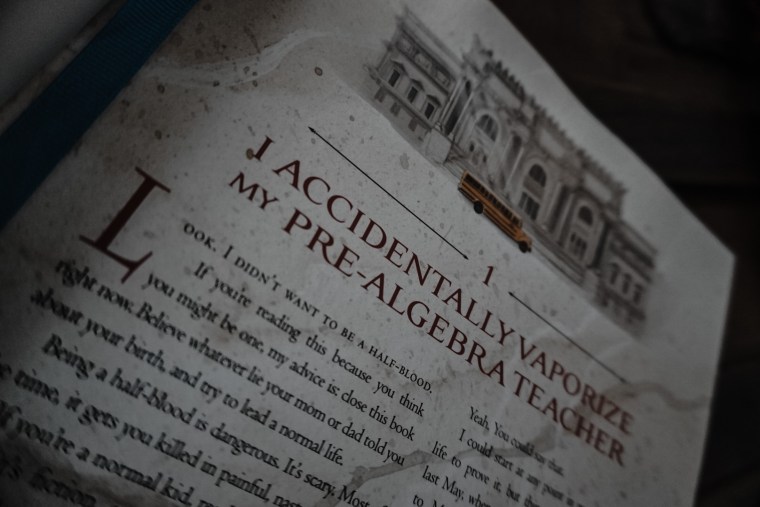

I’ve read The Lightning Thief so many times that my original copy is falling apart. Pages are falling out, edges torn, spine cracked, and all the usual signs of a well-read book. However, I have the illustrated version, which I bought for myself in 2018 because it came out on my birthday. I never read through that edition, so the stars aligned. It’s technically a “new” book.

Maybe my resolution is still intact after all?

If you’ve been living under a rock since 2005, The Lightning Thief is the first book in Rick Riordan’s middle-school series Percy Jackson and the Olympians. TLT follows 12-year-old Percy Jackson as he learns the Greek gods are real and he’s proof. His dad is an Olympian (an important one), which means Percy’s life will be anything but easy.

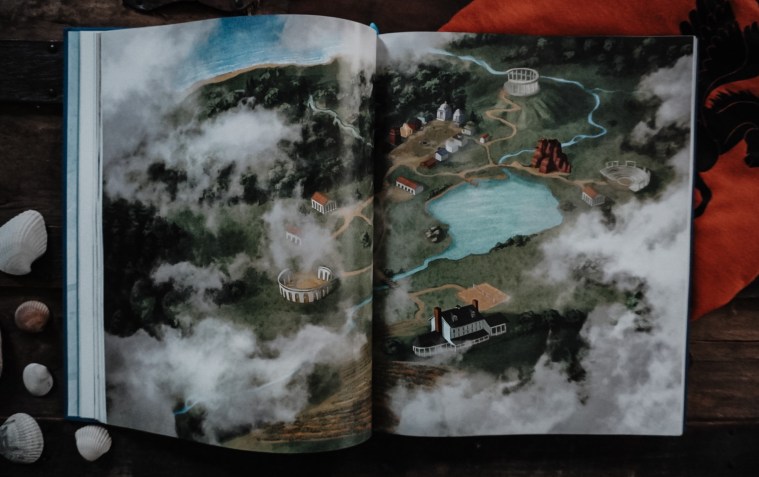

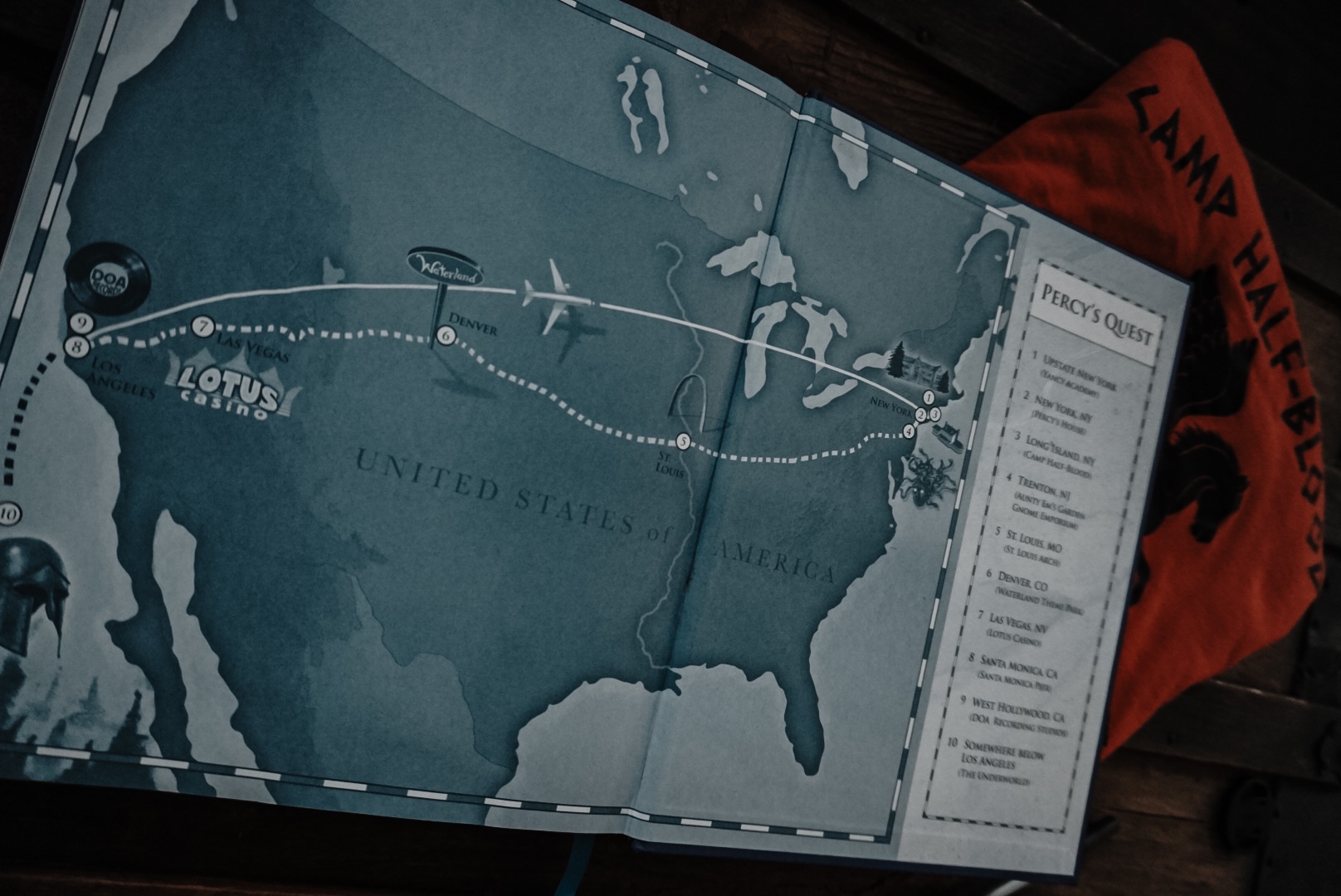

Percy, along with his satyr friend Grover Underwood and Daughter of Athena Annabeth Chase, have 10 days to travel across the country, dodge a flurry of monsters, visit the underworld, save his mom and stop a war from breaking out among the gods.

And that’s only the beginning for our young hero.

Here are all my thoughts on The Lightning Thief.

(Warning: Because I have already read ALL of Riordan’s books, there will be plenty of spoilers for more than just TLT.)

Enough tears to fill the River Styx

I feel like I’ve said this several times before, but I will continue to say it for the rest of eternity. The Lightning Thief is one of my favorite books of all time. (I even have a tattoo inspired by it.)

It sits rightfully in the No. 2 spot, right behind To Kill a Mockingbird. While it’s No. 2 on that list, it’s No. 1 on my list of most-read books. I’ve read the entirety of PJO dozens of times. They are truly my comfort books, and TLT is just absolute perfection.

I first read TLT when I was 12, the same age as Percy in the book. I remember sobbing over Annabeth, because that was the first time I saw myself in a book — a little girl with ADHD, big aspirations, a bit of an attitude problem, a love for learning and maybe a little annoyingly prideful.

For my entire life since, Annabeth and Percy have been my comfort characters. Through every stage of life, I’ve seen pieces of myself in them and them in myself.

The Lightning Thief is very much the book that has affected my life the most. It’s very dear to me.

I used to read PJO once a year until my junior year of college. That’s the last time I read the series. That was about five-ish years ago.

Even after all this time, I was overjoyed to know I still could recite the first couple pages without even looking at the page.

“Look. I didn’t want to be a half-blood,” is by far the most iconic opening line of a book. You can fight me on that. AND! If it’s not the opening line of the TV series, I will fight Rick Riordan and the entirety of Disney myself.

Mark my words.

Anyway, going into my reread, I was really curious if my love for PJO would remain true or if I would find too many faults with this piece of literature that I hold so close to my heart. I was so worried I would close the book, hating it. (That’s the reason I waited like seven years to read To Kill a Mockingbird a second time. I didn’t want my love for it tainted.)

Good news! While I did find some questionable choices by ole Uncle Rick, The Lightning Thief made 25-year-old me just as emotional as 12-year-old me. I love it just as much as ever — maybe even more, because I really took my time to think about the text and look into its literary elements.

For being a middle-grade book, it’s surprisingly thoughtful.

I am not a better (wo)man

I wish I could sit back and pretend I have the moral high ground on this, but I can’t. There’s a really good chance I would’ve chosen to join Luke Castellan on Kronos’ side. Not a fan of the gods, my guys.

That’s probably my biggest takeaway after this reread.

As the PJO series unfolds, Luke becomes more and more Percy’s foil; however, it is in TLT that the foundation is laid for this literary device.

Let’s start with Luke.

Luke never hides his casual resentment toward the gods, because he doesn’t have to.

Even Annabeth, who is only 12 and still wants to please Athena, tells Percy this on his first conscious day at Camp Half-Blood: “They have a lot of kids and they don’t always … Well, sometimes they don’t care about us, Percy.” The fact the gods don’t care for their children isn’t a secret. The kids know their place.

Throughout TLT, the reader gets more and more details about why Luke is so bitter over this.

His quest to take a Golden Apple from the Garden of Hesperides was just Hermes’ way of trying to appease his son. Hermes threw Luke a bone, but he didn’t want a quest for quest’s sake. He wanted to actually be needed by his father — to be recognized for all the work and effort he’d put into training. He didn’t want an easy repeat of a quest.

The gods think their children want glory, but they just want to be appreciated and allowed to survive a life they didn’t choose.

This is why it’s so incredibly important for Luke to be in the young adult age range of 19-23/24 in the series.

He’s lived longer than most Greek demigods. The gods expect that to be enough for him, and it simply isn’t. He’s not willing to settle for that, because he’s seen and experienced the injustices the gods have dealt their children. He’s had enough.

Luke isn’t a scorned, scared 12-year-old boy looking for approval from his godly parent.

He’s an adult. He’s fought and bled for the gods, who expect him to be content with being alive through no assistance of theirs. Luke has stood by for far too long, and, after years of feeling helpless against the gods, he believes he’s found the solution to end the suffering.

As readers, we see glimpses of this same mindset in Percy.

When Annabeth confesses the gods don’t care about the kids, he remembers about how a lot of the Hermes campers look “sullen and depressed” like the rich kids he’s met at boarding schools that have been shuffled around. He immediately thinks the gods should be better.

When Chiron tells Percy that Posiedon claiming him was no accident, he’s conflicted.

“I didn’t know whether to feel resentful or grateful or happy or angry. Poseidon had ignored me for twelve years. Now suddenly he needed me.”

Again, when Percy, Annabeth and Grover head out on their quest, Percy’s inner-monologue reflects his discomfort and confusion over his godly parentage.

“The truth was, I didn’t care about retrieving Zeus’s lightning bolt, or saving the world, or even helping my father out of trouble. The more I thought about it, I resented Poseidon for never visiting me, never helping my mom, never even sending a lousy child-support check. He’d only claimed me because he needed a job done.”

A part of me wondered if perhaps being so close to Luke in his first days at Camp influenced Percy’s way of thinking about Poseidon. However, Percy’s feelings are extremely valid, and he learns the same lesson that Luke has.

He is a pawn in the gods’ petty games.

When the Master Bolt appears in his backpack in the Underworld, Percy thinks, “But suddenly the world turned sideways. I realized I’d been played with.”

Ares tricked him to attempt to start a war, but his father sent him on a quest to handle a petty argument between himself and Zeus that led to his son being hunted by Hades’ monsters.

The gods don’t care about his life, they care about their own power and pride.

It’s in this moment of realization that Percy and Luke become foils.

We are officially presented with two young boys, who have risked their lives for the gods’ frivolousness and now refuse to face future manipulation.

However, Luke is still being manipulated. Kronos has used Luke’s insecurities against him to get the son of Hermes on his side to do what he cannot. In return, Luke does to Percy what the gods and Kronos have done to him.

Luke gave Percy the flying shoes that were meant to drag him to Tartarus. He betrayed him and attempted to murder him several times. In a way, Luke is worse than the gods. The gods never pretended to befriend their children. They always kept their distance.

While Luke has turned to Kronos’ plan of destroying the gods to solve the problem at hand, Percy decides that he wants to be a hero on his own terms. Despite the betrayal, Percy still wants to protect the world and the Camp that has become the one place he’s felt safe and at home.

I do want to point out that what sets Luke apart is that he’s had nearly his entire life ripped apart by the gods, which we find out more about in later books. He watches Thalia be hunted by monsters and sacrifice herself, but his mother was also mentally unwell due to her attempt to become the new oracle. While Percy has his mom, Grover and Annabeth; Luke really has no one. He doesn’t have the same support system as Percy.

Instead, Luke has the responsibility of taking care of a cabin full of reasons the gods have failed.

Big 3 Energy

For the first time, I noticed how much Percy thinks about Thalia Grace in The Lightning Thief. He relates to her sacrifice, because, as we learn later but see evidence of even in book No. 1, Percy’s fatal flaw is loyalty. He would also sacrifice himself to save his friends.

It’s more than just her sacrifice that strikes something within Percy.

Thalia was hunted her entire life for simply existing as a child of the Big Three.

Percy has also been hunted, even if he’s just now realizing it.

He starts to remember all the strange things he’s encountered throughout his life that have been contorted by the Mist — like a snake in his cot in preschool or the cyclops that stalked him on the playground in the third grade. He’d been suspended and bumped around schools because of monsters, not necessarily because he was a troubled kid.

The gods were meddling in his life long before he knew they existed.

Thalia was just a little girl, the same age Percy is in TLT, and the gods punished her for her godly parent’s mistake. Hades sent his worst monsters after Thalia, and he did the same thing to Percy.

Thalia was retaliation for Zeus killing Maria di Angelo, the mortal mother of Nico and Bianca, who Zeus tried to murder despite them being born before the oath.

Thalia, and later Nico and Bianca, are proof that the gods will stop at nothing to protect their positions of power and hold their own pettiness higher than the lives of their children.

Percy thinks about Thalia. He even dreams of her.

He dreams that he’s being forced to take a standardized test while wearing a straightjacket, and Thalia is next to him in the same predicament. She says to him, “Well, Seaweed Brain? One of us has to get out of here.”

It’s her words that push Percy to pull himself out of that dream and back into the cavern, where he believes he can speak with Hades — only it isn’t Hades. That isn’t important, yet. What’s important is that Percy sees Thalia and it’s a motivator for him.

To me, this pointed to him wanting to do right by her. She was a child of the Big Three who didn’t survive, and he will do whatever it takes to survive on her behalf. He will beat the odds and make a difference for the girl so much like him, who didn’t get a chance to live.

This is something Percy brings up when he realizes that Luke is the one who betrayed him. In Percy’s mind, Thalia gave her life to save Luke’s and this alignment with Kronos doing her sacrifice a disservice. Percy wants to honor Thalia’s memory by surviving, while Luke wants to destroy the gods for allowing her to die.

Both are valid.

Luke has a right to be angry for what happened to Thalia. The gods had her hunted down and murdered. That’s royally messed up.

I also see why Percy thinks that he can honor her by fighting and going about his life as normal. The gods win if he dies. He can live, fight for what’s right, and try to make the gods change their ways so that other demigods don’t have to face what he and Thalia have gone through.

He can show them that the children of the Big Three aren’t weapons that need to be hidden and destroyed. They are assets. They are children. They deserve to live.

Which brings me to my next point …

Zero to Hero

In TLT, a huge overlying theme is heroism.

At first, Percy has no real interest in being a hero. He just wants his mom back.

There’s also the underlying wants that Percy has that are sort of buried under the plot. He wants somewhere to belong. He wants to feel safe. He wants to not feel like a burden.

Those are aspects of Percy’s personality that we see from the very first chapter. On the very first page, he throws out: “Am I a troubled kid? Yeah. You could say that. I could start at any point in my short miserable life to prove it …”

Percy doesn’t think of himself as a hero. He sees himself as a troubled kid, as somebody that people don’t want around, as stupid and worthless.

These insecurities are a constant throughout the series and into the sequel series, as well. Percy never sees himself the way others do. He doesn’t think of himself as a powerful demigod; he thinks of himself as a 12-year-old boy, who struggles to read, can’t focus, and got kicked out of school for the sixth time in six years.

Not hero material.

He also doesn’t care that he’s a child of the Big Three. In fact, there’s moments where he misses the comradery of being in the Hermes cabin. He feels alone, isolated and scrutinized as a son of Poseidon; because Percy Jackson never cared about whether or not he was a hero or the best, he just wanted to belong. He wanted to be safe. He wanted the people he loved to be safe.

However, we see that change throughout TLT. As Percy is more immersed into this world of mythology, he finds a home, he finds friends, he finds a family, and he finds a cause worth being a hero for.

“You have completed your quest, child. That is all you need to do.”

“But—”

I honestly love this moment between Percy and Poseidon, because it’s such a short little quip but it delivers so much of Percy’s character and his dynamic with his father.

He wants to discuss Kronos rising, because he wants to protect this world and the people he loves that are in it.

He didn’t want a quest for the sake of successfully completing a quest.

Percy wants to be a hero.

And, with this discussion, Poseidon sees that in his son, and I think it worries him. He gives us this line (Poseidon will not be winning any dad of the year awards any time soon):

“I am sorry you were born, child. I have brought you a hero’s fate, and a hero’s fate is never happy. It is never anything but tragic.”

The delivery is awful, but the sentiment is there. How many of his demigod children has Poseidon seen become great heroes only to fall to terrible fates because of their entanglements with the gods?

He doesn’t want that for Percy, who is now seeking out a hero’s fate on his own accord. It’s one thing to be ready for when the gods call on you, it’s another to want to throw yourself into the belly of the beast willingly.

This is Percy accepting a hero’s fate, and Poseidon wants to delay it as long as possible.

Sally has also been delaying her son’s fate, but she has come to terms with the fact that her son has chosen a path for himself.

“You’ll be a hero, Percy. You’ll be the greatest of all.”

Instead of pushing Percy away from his hero’s quest, she leans into it.

He will be a hero. He’ll be the greatest. And, just like his namesake Perseus, he will have a happy ending.

That was a choice

The Lightning Thief was published in 2005.

That’s important.

And it’s very obvious with some of Riordan’s choices.

The thing that stuck out most to me was Luke’s age. He’s 19. I like that he’s in the age range of young adult, rather than middle school. It’s important for the story as it moves forward. However, in TLT, readers see that Annabeth has a bit of a crush on him. She blushes and stares and stammers around Luke, which is very un-Annabeth.

This isn’t the problem. It’s okay for Annabeth to have a crush. She’s 12, and Luke has been the one constant in her life for five years. He saved her life with Thalia. They share the trauma of losing the daughter of Zeus. It makes sense for Annabeth to crush on him.

What I don’t like is that in the final book, The Last Olympian, Luke asks Annabeth if she loved him. She admits her old crush but that she saw him as a brother, to which this 20-something-year-old FLINCHES. He flinches!

At that time, she was 16 and he was 23-ish. *barfs* It just seems like such a weird thing. It’s icky to think about. I didn’t like it one bit, and there’s such an easy out for this situation. You focus on the love derived from that promise they made as a found family, rather than romantic feelings between an adult and a child.

Weird choice. Easily avoidable. Did not enjoy.

My other glaring issue with TLT was Riordan’s depiction of World War II being a battle between the children of Zeus and Poseidon against the children of Hades leading to the oath to not have any more kids.

It just felt like a poor decision. Riordan is implying that children of Hades led the Nazis into war.

Once again, it’s a weird choice. I like the concept of tying mythology into modern history. It makes sense that the gods would like to prevent their children from influencing and changing the course of human history to such a drastic degree. However, the execution is questionable.

Yes, you can say it trivializes a literal genocide or that it minimizes the impact of World War II. However, it also just doesn’t fit in with the plot.

Riordan spends so much page time trying to show that Hades and his children are not villains. Even in The Lightning Thief, Percy’s first instinct is to blame Hades for stealing the Master Bolt because of the stigma around the god of the underworld. He learns that his own prior misconceptions allowed for him to be misled. He relates to Hades being outcasted by the other gods.

It feels odd to have this arc while knowing the World War II bit of information. What message is Riordan trying to send? Doesn’t feel like a good one after my reread.

I like to offer a solution to my critiques, and this one is tough. I’m not sure there’s another world-altering event big enough to explain why Zeus, Poseidon and Hades would swear an oath to not have any more children. Perhaps this idea could’ve been reworked to play with the concept that the demigods’ fight was covered up or concealed by the events of World War II, but still showed how the Big Three kids held far too much power.

As much as I adore The Lightning Thief, Riordan made questionable choices in writing, and they deserve to be called out. Don’t get me started on The Heroes of Olympus or Magnus Chase and the Gods of Asgard series. Those are somehow messier.

Final Review

The Lightning Thief is a proper middle-grade romp of a novel. It’s a new-age classic. It’s a book that will live on as one of the best of this generation.

OK, maybe I’m a bit biased.

I will stand behind those words, though.

I think TLT is a marvel of a book.

Percy as a first-person narrator is witty, funny and relatable. He’s a child struggling to find his place in a world that doesn’t make sense — a journey so many middle schoolers can see themselves in.

The mythical world isn’t too complex, but also well-built and explained perfectly through the lens of Percy learning the mechanics alongside the reader.

Throughout Percy’s exciting quest to the Underworld, readers are delivered a series of lessons about acceptance, family, loyalty, heroism and what it means to take control of your own fate.

However, it is glaringly a book written in 2005. Author Rick Riordan made some unique choices in plot details that are questionable at best. While those choices do cause some eyebrows to raise, they don’t take away from the wonderful story laid out.

Overall, The Lightning Thief is an impeccable middle-grade novel that can be enjoyed and loved by readers of all ages. It’s a timeless classic that will see new life thanks to the upcoming TV show that will hopefully erase the tainted legacy of those awful movies.

10 billion blue tortilla chips out of five.

Leave a comment