I get the hype.

Six of Crows by Leigh Bardugo got me. It got me good.

But it wasn’t love at first line.

I went in with high expectations, which tends to leave me disappointed. I was actually prepared to be disappointed with this duology that has flooded every single one of my social media feeds.

It was disappointing at first. I just couldn’t get into it. It took me almost two weeks to get halfway through this book, but then I demolished the rest in two days.

This is the point where I usually give a little synopsis of the book, but I like what the front cover gives: “Six dangerous outcasts. One impossible heist.”

I lied, here’s a little synopsis:

Six of Crows is a dark adventure comedy full of traumatic backstories and endless banter from morally gray teens forced together by tragedy and kept together by greed, loyalty and a whole lot of unspoken love.

Here are all my thoughts on Six of Crows.

Who are you? Where are we? What’s going on?????

We’ll get my biggest gripe out of the way first.

The world building in Six of Crows was a dumpster fire.

I understand the Shadow and Bone trilogy came first, but literally every single person I asked said I didn’t need to read it to understand and enjoy the duology. Maybe Shadow and Bone does a better job at establishing the mechanics of this world, so I’m willing to give a bit of leadway into how this affects my overall opinion of the book.

However, I believe that, if your goal is to create a unique story that’s not a direct continuation of the previous books, you should put in the same effort of world building.

I think it’s something that Cassandra Clare does exceptionally well throughout her Shadowhunter Chronicles. You can start with any series and have the fundamentals of the world. That being said, Clare’s Shadow World is low, urban fantasy; while Bardugo is more high fantasy that requires more establishing.

The issue is that Bardugo did the bare minimum world building in Six of Crows, and it immediately took me out of the story.

We start with the POV of some guy named Joost. Am I supposed to know who he is? The same goes for Anya. I just didn’t know who these people were, but the narration was so casual and elusive that it felt like I should. Are they characters from Shadow and Bone?

We never hear from Joost or Anya again, except for a vague mention of the fate of the first Grisha to die of jurda parem.

I understand the importance of the opening scene. It sets the table for the conflict and gives readers a sense of dread by knowing the power of this drug. I just wish Bardugo did this with characters specific to this duology.

Also, Nina Zenik was a soldier in the Second Army, but the details of the war are never truly fleshed out. I literally know nothing about Shadow and Bone, but I’m going to guess it deals with the war. If not, that would make me even angrier.

As a new reader, I didn’t know what the Second Army was, who they were fighting or what they were fighting for.

It was little details, especially at the beginning, that were eluded to rather than explained that simply pulled me out of the story because I didn’t know what was going on.

I’m willing to forgive this misstep, because once I got past it, I was hooked.

It’s just a fabulous story.

The characters are complex and flawed and my favorite shade of morally gray; but Six of Crows isn’t primarily character driven.

I’m harsh on plots, and this is one of the best plot lines I’ve read in a long time. I loved the thrill of the heist. My heart was hammering as the crew made its way through the Ice Court, and I was trying to figure out the next step in the plan for myself before it was revealed.

It was so intricate. Everything mattered. Everything had a purpose.

Plus, it was so much fun to try to guess whether something that happened was just coincidence or part of Kaz’s plan, because Bardugo did such a fabulous job at making the mystery a part of the character’s own lore. All of the characters were just as in the dark as the reader, which felt oddly satisfying when it should’ve been infuriating.

As for the ending, it was fine.

The Crows are double crossed by Van Eck, which I sort of saw coming because nothing about this story told me there’d be a happy ending. There are no happy endings in the Barrel. Also Van Eck gave me the heebie jeebies more than Kaz ever did. Their whole meeting felt off at the beginning, which is why I was surprised that Kaz didn’t have a more fool proof plan to seal the bag.

It did fit in with the themes of the story about morality and class, though.

Kaz trusted Van Eck’s offer was legit, because he’s a wealthy merchant and therefore held to a certain standard that the Dregs are not.

This moment really brings the story together in blurring the lines of morality. Kaz essentially loses because he has more heart and honor than Van Eck, which is the opposite of how these two started their deal. It was a full-circle moment that was both a perfect wrapup for book No. 1 and a great leadway into book No. 2.

Crows in a Barrel

I am a slut for symbolism.

Sorry for being lewd, but it’s absolutely necessary.

Six of Crows gave me so much good symbolism that made me high-key feral putting it all together.

Kaz is the pseudo-leader of the Dregs, one of the many gangs in the fictional city of Ketterdam. According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, dreg has three definitions but only one is really relevant in this instance: “the most undesirable part.”

The Dregs are made up of mostly young, petty criminals. Before Kaz came along with his mission of vengeance, the Dregs were “a laughingstock, street kids and washed-up cadgers running shell games and penny-poor cons out of a run-down house in the worst part of the Barrel.” The Dregs were quite literally the “most undesirable” gang in the “most undesirable part” of Ketterdam.

That makes me think, which came first, the name or the reputation?

The name Dregs is symbolic of the class system in effect in the city. These kids were brought together by traumatic circumstances — slave trade, addiction, death, war, discrimination. They had nothing to give but their morality, which they used as currency in the Barrel in order to survive. They did not have money or status or power. They were already the dregs of society, so why not join a gang that represents who you are?

The Dregs is more than just a name, it’s a reflection of their status in society and their rank in the Barrel.

Additionally, the Barrel is symbolic of the characters’ entrapment in Ketterdam. They are bound under contracts and debts, by guilt, by loyalty and by heartbreak.

I saw the Barrel as a reference to the phrase, “easy as shooting fish in a barrel”.

Because of their shortcomings, the Dregs are caught in the Barrel, which makes them easy targets for more powerful people (i.e. Pekka Rollins, Per Haskell and Van Eck) to exploit their desperation.

Inej thinks about this on the roof of the Ice Court as the Crows prepare to launch their second plan.

“What bound them together? Greed? Desperation? Was it just the knowledge that if one or all of them disappeared tonight, no one would come looking?” (332)

She understands that they are all similar in their shared sense of aloneness and trauma and what it has driven them to do.

Van Eck knew it, also, which is why he chose them for the job of “rescuing” Bo Yul-Bayur in the first place. He even gives a statement very similar to Inej’s own thoughts.

“Oh, you are resourceful and far more clever than any mercenaries, I give you that. But more important, you will not be missed. … All of you will vanish, and nobody will care.” (446)

It’s also how Kaz convinced Inej, Jesper, Nina, Matthias and Wylan to be his team for the mission.

“You see, every man is a safe, a vault of secrets and longings. Now, there are those who take the brute’s way, but I prefer a gentler approach — the right pressure applied at the right moment, in the right place.” (45)

They’re fish in a barrel.

Somebody is always going to be taking easy shots at them. It’s the same thing day in and day out; risk your life just to risk it again the next to pay a debt that will never be settled.

Kaz knows this, and, while he seemingly gives everyone a choice to be a part of this heist, they don’t really have one. They all want something and that something makes them susceptible for manipulation or, at the bare minimum, easy to convince.

The heist offers a chance to get out of the Barrel and to stop being an easy target, so they take it. They have to, so they can leave the Barrel for good and end the cycle of suffering. Or in Kaz’s case, find the revenge that he believes will heal his broken heart from the loss of his brother — not that he’d use those words, of course.

To round out this section, let’s talk about the literary symbolism of crows!

Crows are some of the most overused pieces of symbolism in literature and are fairly interchangeable with ravens, but I liked the way Bardugo uses it, so I’m allowing it. Fun fact: Crows are found in every continent except Antarctica, which is probably why they’re universally depicted in literature, pop culture, religion and mythology.

Ravens, crows and other birds of prey have annotations of death and darkness. They often symbolize bad omens or dark magic, and are often associated with trickery, intelligence and vengeance — all attributes that encompass Bardugo’s characters and their stories.

In Greek mythology, a white raven/crow told Apollo of the infidelity of Coronis, which led to the god of Prophecy scorching the bird with a curse for his lover, turning the bird’s feathers black and setting the tone that crows were deliverers of bad news.

Crows are also representative of Morrigan, the goddess of war and death, in Irish mythology.

Crows are found throughout different cultures in a variety of ways, but commonly as symbols of spiritual transitions (especially in the Native American traditions of the crow clans of the Hopi, Chippewa, Pueblo, and Menominee tribes).

Bardugo’s Crows all go through some form of emotional/spiritual transition throughout this novel, which I’ll actually get into more in the next part.

They are born one person, transform into another via trauma, remold themselves in Ketterdam, change who they are again in the Barrel to survive, and figure out who they want to be during the Ice Court heist.

In conclusion, the way Bardugo crafted the symbolism of crows into the characters’ story arc was very intriguing, and I wonder if she’ll continue to find ways to do so.

Side note! I did way too much research on the significance of crows, so here’s some more interesting tidbits: There’s superstitions based around the number of crows you come across. Six crows is a symbol of bad luck, particululary, if you see six crows outside of your house, it indicates a burglary. Whereas, five crows mean death or sickness is lurking and four crows represent wealth and prosperity. Is this foreshadowing? Will two Crows need to die to get the 30 million kruge?

And finally, the Crows’ motto of “No mourners. No funerals.” is ironic, because crows are peculiar in that they are known to investigate the deaths of one of their own. I remember learning this in middle school, and double-checked good ole Wikipedia (and the cited sources) to make sure it wasn’t a fever dream. It’s not exactly a funeral, but they do gather to figure out what caused their fallen comrade’s death, which is endearing in its own way. They look out for each other.

Some references I used:

Crows and Spirituality — cites all their sources, which we love. I also checked a few similar sources just to make sure it was cohesive/correct.

Reference book for mythology — I own a copy of this book, but I found a way to link it.

The Barrel Bunch

Transformation is at the forefront of Six of Crows, with our six main character undergoing various stages of change throughout the text as they process their past traumas, cope with their current predicaments and discover who it is they want to be — or why they’re risking their lives for such a high-risk heist in the first place.

Despite Kaz’s reputation of being the bastard of the Barrel, none of our characters are actually born in Ketterdam. They all led different lives prior to their arrival in the city.

“A gambler, a convict, a wayward son, a lost Grisha, a Suli girl who had become a killer, a boy from the Barrel who had become something worse.” (Inej, 332)

This observation by Inej is a very boiled down version of who this crew truly is, and I noticed that she mentions the changes in herself and Kaz but none of the others. Inej acknowledges that she and Kaz are similar in that they’ve transformed into something awful to survive, which says a lot about her priorities.

But that is beside the point.

The point is that these characters are complex and only get more intricate as readers get more of their stories.

For the sake of time, I’ve chosen to dive into only Inej and Kaz’s transformations. However, maybe I’ll write some mini essays on the others in the future.

Inej

This needs to be screamed from the rooftops: INEJ HAS SOME OF THE BEST CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT IN ALL OF LITERATURE! IN ONE SINGLE BOOK!

It is truly incredible. I felt almost honored to witness her journey, and it made me tear up on more than one occasion.

Through Inej’s memories, we see how she was kidnapped from her family’s caravan at 14 and sold to Tante Heleen, who runs the pleasure house the Menagerie. She was tricked into a contract she would never be able to pay off and abused by Heleen and her clients. She was very scared and felt hopeless in her position.

Yet, when Kaz walks into the Menagerie seeking information from Heleen, Inej finds the courage to speak up to him offering what she knows.

I loved this moment. I believe it did a great job at showing how brave Inej was, even before the armor of the Wraith. No matter how scared she was, she was not entirely helpless. She was stealthy, able to sneak up on Kaz despite the bells on her ankles and her silks, and she was willing to give information.

This leads to Kaz convincing Haskell to buy out Inej’s contract at the Menagerie.

He didn’t see her as a scared girl to be taken advantage of, he saw her as useful and dangerous.

“Dangerous. She wanted to clutch the word to her.” (308)

I found this personal confession and interaction with Kaz interesting, because it creates a bridge for Inej’s transformation into the Wraith. She’s already dangerous, but she didn’t see that part of herself until Kaz spoke it into existence. She hears the word and she wants to be dangerous, but in a way where she can’t be hurt any further. It’s the allure of the Dregs to be something/someone she wants to be.

This desire to be dangerous, along with her skills built up as an acrobat and her deep faith in the Saints, allows Inej to use her past to move toward her future, which means she must do what she needs to survive in the present.

Inej chooses to join the Dregs, which may be the first choice she’s made for herself in her entire life. In doing so, she gives herself over to Kaz to transform her into the dangerous Wraith, stealer of secrets and life.

“I’m already a ghost. I died in the hold of a slaver ship.” (Inej, 307)

This quote is just *chef’s kisses*. It’s reflective of how Inej sees herself prior to joining the Dregs. She’s a shell of who she was, and the Wraith allows her to regain an identity for herself. Once again, it points to Inej already believing she had the capability to be what Kaz needed. She’s already dangerous. She’s already a ghost.

As the Wraith, Inej becomes skilled with knives and even calls them her claws, which ties back to her time as “the lynx” at the Menagerie. It’s symbolic of her taking control of her image.

We see several times throughout the novel where Inej is desperate for control over herself.

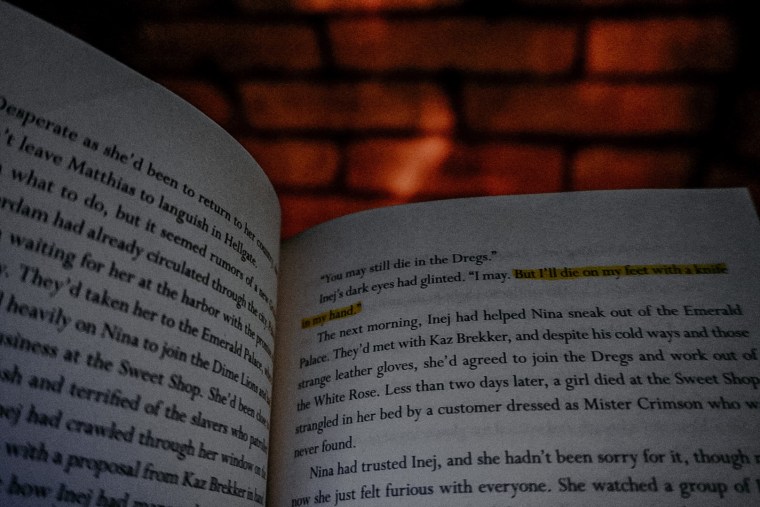

Once Kaz freed her of the Menagerie, it became her mission to fight to maintain her own freedom in any way she could. She tells Nina that, while she is still indebted in the Barrel, she can now die while fighting — which is its own form of freedom. Then Inej nearly takes her own life when she’s bleeding out on the docks, because she’d rather die than be captured. This is something she considers again at the end of the book when the Crows are faced with an army of Fjerdan.

All Inej ever wants is control over her own life — how she lives it and how it ends.

This is probably why she holds her faith so dearly. It grounds her to the person she wants to be, the person she was before being kidnapped, the person she really can’t be in the Barrel. She doesn’t have much control over her actions, but she has control over the basis of her soul that makes justifications for her actions.

There’s a scene at the very beginning of the book where Inej counts the men she murders and then considers their lives something she needs to pay penance for.

It coincides with the topic of moral ambiguity that surrounds the text.

She struggles with what killing and thieving has done to her in the eyes of the Saints. Will they forgive her for doing what she needs to survive the Barrel? Can she even return home and face her family after everything she’s done?

She prayed to the Saints, honored them and kept them close; but is she still worthy of their blessings?

Inej has a beautiful moment of self reflection in the incinerator shaft where she considers falling.

She goes through the events of her life that landed her in that exact position. She blames herself at first for becoming the Wraith and what falling would cost the rest of the Crows.

Then she realizes that the reason they’re all together and in this situation is because of Kaz. He agreed to the heist, he made them what they are and he brought them to the Ice Court.

She recognizes that she followed Kaz because she didn’t know who she was and he gave her the things she wanted — a little bit of freedom, an escape from the Menagerie, the right to be armed and dangerous. There also might be some more complicated affectionate feelings involved, but like the characters in this book, we’re not talking about them.

All this time, Inej has been fighting for Kaz and what Kaz wants. In that incinerator shaft, she realizes her own dream of setting sail to murder slavers so she can protect others like herself from the fate she endured.

“She was not a lynx or a spider or even the Wraith. She was Inej Ghafa, and her future was waiting above.” (311)

This reflection gives her life purpose outside of just paying off her indenture and escaping the Barrel. She takes the pieces of the people she was and claims an identity all her own, not one made for her like the lynx or the Wraith.

In doing so, she’s more determined for this heist, but also more confident in her feelings.

When Kaz gathers the nerve to ask Inej to stay in the Barrel with him, she declines.

“I will have you without armor, Kaz Brekker. Or I will not have you at all.” (Inej, 434)

Kaz is not willing to give Inej all of himself. He’s not willing to share the traumas that make him flinch away from touch, which is his right to withhold. However, Inej is allowed to deny him her heart because of it.

This points back to when Inej remembers a story her father told her about love early in the novel:

“Many boys will bring you flowers. But someday you’ll meet a boy who will learn your favorite flower, your favorite song, your favorite sweet. And even if he is too poor to give you any of them, it won’t matter because he will have taken the time to know you as no one else does. Only that boy earns your heart.” (136)

In the Barrel, there’s not a lot of room for flowers and sweets, instead Inej wants Kaz to treat her as more than just an investment and to see what her heart yearns for — true freedom. These are things he’s not openly willing to do, and she is so justified to walk away. It shows her immaculate strength.

Inej spent the entire book trying to figure out who she is and who she wants to be. She figured it out, knows what she deserves, and she’s not accepting anything less.

“The heart is an arrow. It demands aim to land true.” (135)

Inej is a badass. I respect her so much. I wish I could’ve read this book like eight years ago, because 17-year-old me needed an Inej to remind her how to be a bad bitch who knows what she deserves and doesn’t settle for less.

Kaz

Kaz is such an interesting character to dissect because he’s an absolute sham.

He’s built himself into a living legend where nothing about his personality is real. Thus, as readers, we get a bit of an unreliable narrator situation because we don’t know who our lead man really is or if his actions are part of his own plans or a coincidence.

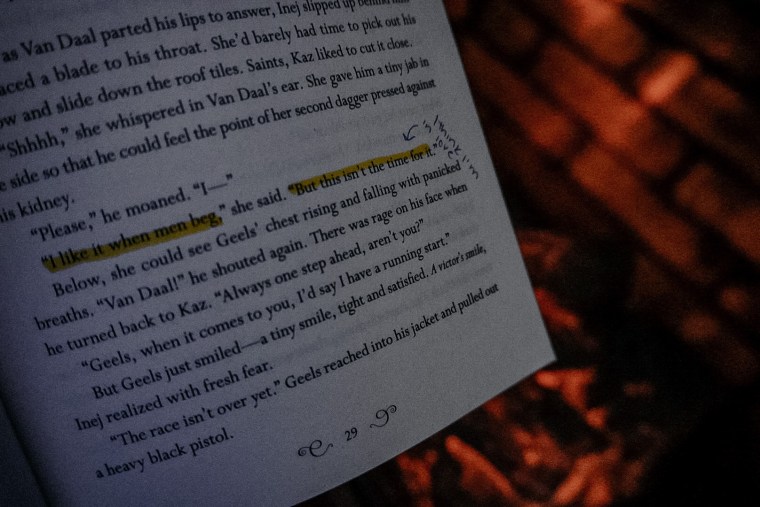

In the opening scene, Bardugo presents readers with the myth of ole Dirtyhands — which is the worst nickname I’ve ever heard and makes me gag — and his base characteristics of being ruthless, motivated, observant, intelligent, cold and callous.

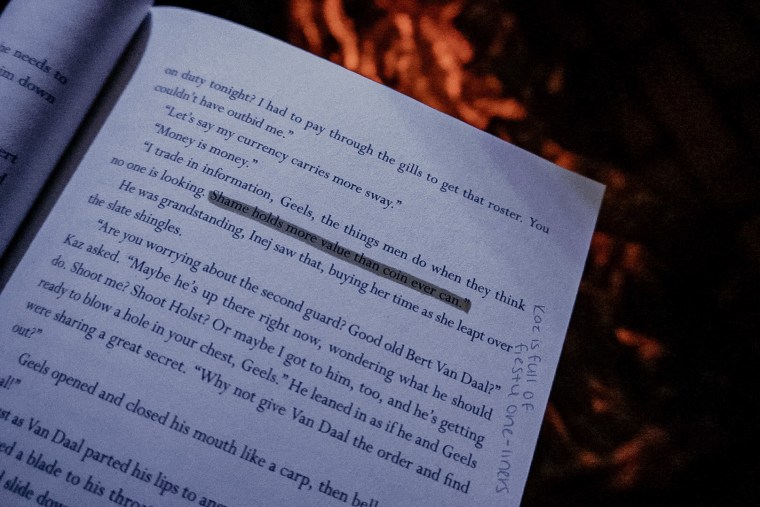

Inej is watching a meeting go down between Kaz and Geels, another mob boss in the Barrel. Through her POV readers get two different perspectives of our leader, because Inej sees through the mask Kaz wears.

See, Kaz is an onion, and we all know from the 2001 cinematic masterpiece Shrek that onions have a lot of layers.

The rest of the Barrel has taken the bait on the costume he has created to earn respect. They see him as a bit of a wild card who commits atrocious acts without reason; however, Inej knows better.

“Every act of violence was deliberate, and every favor came with enough strings attached to stage a puppet show. Kaz always had his reasons.” (Inej, 16)

This opening scene is perfect in showing readers that Kaz is a schemer, he’s smarter than the average Barrel Boy and he expects his team to have a lot of trust in him without giving them the same courtesy. He’s constantly building a never-ending plan that he doesn’t divulge the full details for. He’s collecting information to use later.

The legend grows as the story moves forward.

Kaz kills Oomen even though the man gave up information, and he pops the prisoner’s arm out of its socket just to prove a point (I don’t care what else happens, that scene with the prisoner is the worst thing Kaz has ever done. Sickening.). He even calls Inej, who he has the most affection for, an investment!

Unlike Inej, who holds onto pieces of who she was before the Barrel, Kaz has essentially killed off the boy he used to be.

Through flashbacks, readers discover why Kaz is the way he is and why his motivation is so high.

After their father’s death, Kaz and his older brother Jordie came to Ketterdam where they were properly swindled out of their money by Pekka Rollins under the disguise of genuinity. Jordie died on the street of firepox, and he and Kaz were both put on a sick boat and taken to Reaper’s Barge, where bodies were disposed of.

Kaz, still weak from his own battle with the plague, couldn’t swim back to the Ketterdam harbor alone; so he used Jordie’s body to keep him afloat and alive.

This moment is what Kaz considers his rebirth.

“Barrel boys don’t have parents. We’re born in the harbor and crawl out of the canals.” (Kaz, 433)

Kaz kills off the boy he was before Jordie’s death. He’s no longer Kaz Rietveld, a little boy who’s easily tricked. He’s Kaz Brekker, a ruthless criminal who stops at nothing to get revenge.

This is where the legend of Dirtyhands begins.

I found it interesting how quickly Kaz reshaped himself out of this traumatic incident. It was like a switch flipped inside of him. He had all the ingredients to make a monster already, and Jordie dying forced him to become one — which is something we’ll discuss down below.

Kaz tells everyone that everything he does is for greed and power, but, with the knowledge of Jordie, readers know that he’s doing it for revenge. At first I wondered why he didn’t just outright say it, because a man who’s looking for revenge is terrifying and creates more of a personal rift between Kaz and Pekka. However, a man with seemingly no motivation but his own greed is practically invulnerable and keeping Pekka in the dark is a way for Kaz to strike without the mob boss poking at his insecurities.

It creates an interesting dynamic, almost one-sided between Kaz and Pekka, where, as a reader, I felt a touch of sympathy for Dirtyhands. The man who changed his life for the worse doesn’t recognize him. It’s adding insult to injury and fuel to the already blazing hot fire within this boy, who is hurt so badly but won’t acknowledge it.

Going along with this, is how Kaz turned his insecurities into a weapon.

He lets the grief of losing his big brother fuel his crusade, the black gloves he wears to avoid human touch has become part of his own lore, he turns his boyhood fascination of magic into a useful tool for theft, and, when a broken leg didn’t heal right, he had a specialized cane made that became an extension of both his body and persona.

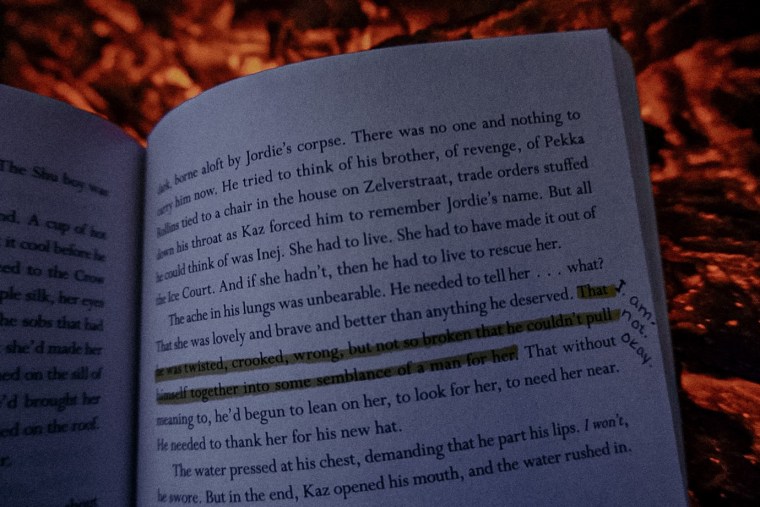

“There was no part of him that was not broken, that had not healed wrong, and there was no part of him that was not stronger for having been broken.” (Kaz, 401)

The above quote gives off an underlying tone of a fragile boy who’s been through too much and has built an armor around himself to protect him from a world that beat the spirit out of him. It goes back to Kaz having two different personalities — the one he shows the world and the one he keeps to himself and tries to hide.

I’m curious if we’ll see more of the hidden personality in Crooked Kingdom because of Inej being kidnapped or if he’ll slip further into his mask. The next logical step for Kaz’s character development would be the stripping of his outward persona, which I don’t want. I want him to get even more ruthless. I want this story to get darker and for Dirtyhands to get dirtier.

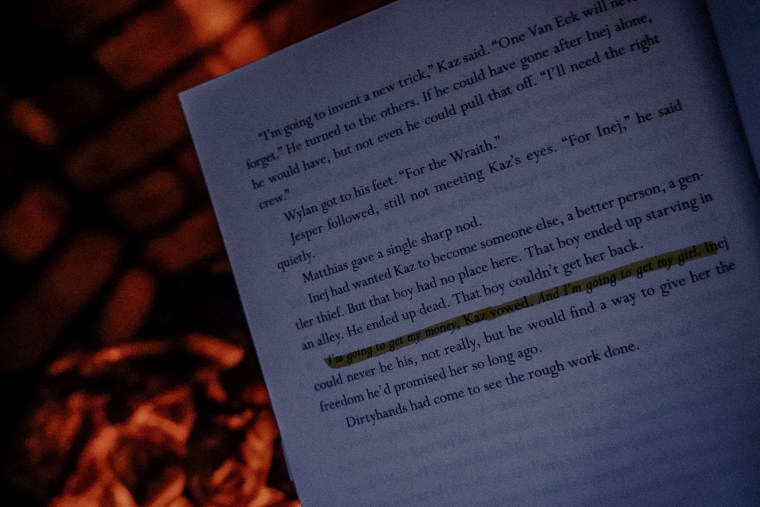

I’m leaning toward getting dirtier because of this passage: “Inej had wanted Kaz to become someone else, a better person, a gentler thief. But that boy had no place here. That boy ended up starving in an alley. He ended up dead. That boy couldn’t get her back.” (456)

Kaz recognized he showed a gentler side of himself by looking at Inej rather than the trunk of money and that led to her being kidnapped. It proves his own theory that there’s no way to give himself to Inej fully while also thriving in the Barrel long enough to get his revenge on Pekka. The softer side of him is a danger to Inej in a place as hostile as the Barrel, and you have to be hardened to fight back.

(Side note! He’s wrong that Inej wanted him to become someone he’s not. She doesn’t want him to turn himself around and become some choir boy. She just wants him to trust her enough with what haunts him at night and to treat her as an equal person rather than an investment.)

However, he still focuses on the idea that he’s getting her back rather than the money, at first. In his head, Kaz always puts Inej first, which is very interesting.

To be honest, Kaz is usually the type of character I cling to, but I didn’t connect with him the way I wanted to. He seemed too over-exaggerated for me. He was a puzzle to solve rather than a character to hold close. He made me a bit uncomfortable, which is probably what Bardugo was going for. So, she got me, I guess.

I want to like him more in Crooked Kingdom. Make me like Kaz more, Bardugo. Do it!

Love disguised as greed

Six of Crows is a love story. Maybe not in the typical sense of the phrase, but definitely where it matters.

Our characters don’t throw around the word ‘love’ very often. There’s not a lot of room for love in the Barrel.

Yet, the overflowing amount of love in the Crows’ actions is overwhelming, but subtle.

Kaz, the least loving person on the outside, may have the most love to give inside. Inej mentions that he used his own money to keep the Slat dry — one of the few places in the Barrel that isn’t a coldy, leaky mess (ew, I’m sorry for even typing that). This shows how Kaz cares for these people who put their trust in him. He gives them a dry place to rest their heads. That means something. It could be seen as Kaz protecting his investment, yet I like to believe he actually wants to take care of the Dregs. He knows what it’s like to live on the streets, to be rained on and cold. He wants to give his gang something better. In return, they give him their loyalty.

Also, when Kaz offered to get Inej out of the Menagerie, he tells her:

“If it were a trick, I’d promise you safety. I’d offer you happiness. I don’t know if that exists in the Barrel, but you’ll find none of it with me.” (308)

He’s honest with her. He doesn’t give her empty promises he can’t keep. That also means something. He cares enough about her to want her on his side on her own merits and not by coercion or trick.

He cared about getting her out of the Menagerie, and her potential gave him the opportunity to do so. This is why he tells her she doesn’t have to bear the silks of the pleasure house in the Ice Court. He’s willing to figure out a new plan if she’s uncomfortable. It’s a gesture that speaks a thousand words in just a few.

The same care and affection can be found in how Kaz chose all of the Crows for the Ice Court heist.

He picks those closest to him — Inej, Jesper and Nina. Sure, he tells them he needs their specific talents for the job, but I’m making the reach that he also chose them so they can turn their lives around and get out of the Barrel with the reward money.

I would even go as far to say that this is why he swaps Matthias out of Hellgate. Kaz knows that Nina cares about Matthias, that she feels guilty for his being imprisoned and that she won’t leave the Barrel without his freedom. So, yes, Kaz needs Matthias for his knowledge of the Ice Court to double-check Wylan’s work, but I think he also wants Nina to be able to find peace afterwards.

As for Wylan, I don’t have much evidence for Kaz choosing him out of affection; however, I believe there’s something to be said about him allowing Wylan to be tailored to look like Kuwei so that he could stand before his father and bear witness to how he speaks of him. Wylan needed that closure to fully cut himself off from his previous life, and Kaz gave that to him.

All of these things are acts of love in their own way, and Kaz uses the disguise of greed and profit. In a place as bastardly as the Barrel, money speaks louder than words and one’s actions make the man.

“Greed is your god, Kaz.”

“No, Inej. Greed bows to me. It is my servant and my lever.” (39)

Kaz can say he lacks motivation aside from money and power all he wants, but his actions are screams in the dark. He cares about the Crow Club, he cares about the Dregs and he cares about avenging his brother — the ultimate show of love on Kaz’s behalf is that for his older brother, who tried so hard to give him a better life.

Other acts of love from other characters are:

- Nina accusing Matthias of being a slaver in order to prevent him from being taken by Grisha, who probably would’ve had him stand trial for his life as a druskelle. He could’ve been executed if Nina hadn’t stepped in.

- Inej deciding she wants to use her reward money to buy a ship to hunt down slavers. She doesn’t want other children to be hurt as she was. While it’s what she feels she needs to cope and heal, it’s also a public service mission in her eyes and heart.

- Kaz not killing Jesper for spilling the beans about the Ice Court heist to one of the Dime Lions. If it was anybody outside of that core five, I honestly believe Kaz would’ve gutted him. I think Kaz is drawn to Jesper because of their similarities — they both grew up farm boys — and he sees a future for Jesper that he can’t see for himself.

- Kaz and the Crows not picking at Wylan’s inability to read. All Wylan’s life he was made to feel inadequate for having a learning disability; but his artistry and knowledge is what makes him a valuable asset to the team. They don’t dwell on what he can’t do; they praise him for what he can do.

Walking the line

There are no heroes in Six of Crows.

That’s what sold me on this story that tiptoes the line of right and wrong.

Morally gray characters are my favorite characters, and I love when a book makes you genuinely want to root for despicable people. It forces the reader to question what makes a character or an action bad or good and who gets to decide where the line between the two is drawn.

So often, the heroes of stories are privileged enough to be good people. The villains often become villains because of tragic events that forced them to do unspeakable things until it was all they knew how to do. It was always a part of them, but now it’s their most prominent part.

That’s how I felt about the Crows.

They aren’t inherently bad people. I wouldn’t even consider them villains.

They’re protagonists disguised as antagonists, (and, yes, there’s a difference between an antagonist and a villain). They and their actions allow moral ambiguity — the uncertainty of what is right and wrong — to be the top theme of Six of Crows.

“If you aren’t born with every advantage, you learn to take your chances.” (Jesper, 194)

In the above quote, Jesper tells this to Wylan, who seemingly ran away from a cushy home to slum it with the Crows in the Barrel. Wylan holds himself to a higher moral standard than the rest of the Crows, at first. Jesper didn’t know that Wylan was emotionally abused by his father for his learning disability, and then shunned as the family heir for not being adequate enough. To the Crows, this is an uppity boy trying to play crook because of his daddy issues.

This one line sums up the morality of the rest of the Crows.

These characters were brought and trapped in Ketterdam by war, slave trade, death, addiction and despair. They had to become what they are in order to survive the Barrel, which is a kill-or-get-killed part of Ketterdam. We saw that with Jordie’s death.

So they kill, they steal, they swindle and sneak; in hopes that one day it will all pay off to get them out of the Barrel (or revenge, if you’re ole Dirtyhands).

All of our characters see themselves and each other as monsters or immoral in some way due to their exploits.

In the Ice Court, Nina notices a wall protecting the White Island was in the shape of an ice dragon and thinks, “In Ravkan stories, monsters waited to be woken by the call of heroes. Well, we’re certainly not heroes. Let’s hope this one stays asleep.” (357)

They know what they do is wrong, because it’s always being pointed out to them. They know their societal status and they know what they’re doing is seen as morally wrong. There’s never really a question of it.

There’s this incredible moment at the beginning of the book where Van Eck has Kaz jumped and tries to give him a speech on morality, while Dirtyhands cleverly pushes back.

“You’re a blackmailer —”

“I broker information.”

“A con artist —”

“I create opportunity.”

“A bawd and a murderer—”

“I don’t run whores, and I kill for a cause.”

“And what cause is that?”

“Same as yours, merch. Profit.” (44)

The thing about the Crows is that they know what they are. However, the wealthier merchs of Ketterdam are just as devious and treacherous as the Dregs, but hide it under the disguise of business.

This conversation immediately blurs the line between antagonists and protagonists, right and wrong, good and bad. Everybody is playing the same game, but by a different set of rules — in this case, rules that are legal and those that are not — based on their class level.

At the end of the novel, it’s discovered that Van Eck never had the authorization of the Council and also was willing to kill his own son in order to pressure Kaz into giving over Kuwei. He tricked Kaz into the Ice Court heist out of his own selfish greed of wanting the profits of jurda parem, not for the servitude of his country by preventing the drug from being mass produced.

How is what Van Eck did any different than the antics of the Barrel?

They swindle and swoon, they feed off insecurities and hardships, they cut corners to make a profit.

They’re all the same face wearing a different mask.

Final Thoughts

Six of Crows is a fantastical puzzle of a book with a thrilling heist at the center of the plot and morally gray characters who transform themselves to survive in an ugly world. It’s a gritty and dark story that blurs the lines of right and wrong. The Crows are criminals, thieves and murderers; but readers find themselves rooting for them to pull off the impossible.

It’s also witty and clever, with never-ending quips and banter that make readers smile despite the grim topics and dreadful events.

Six of Crows made me laugh, it made me cry and it made me think — the essentials for a great book.

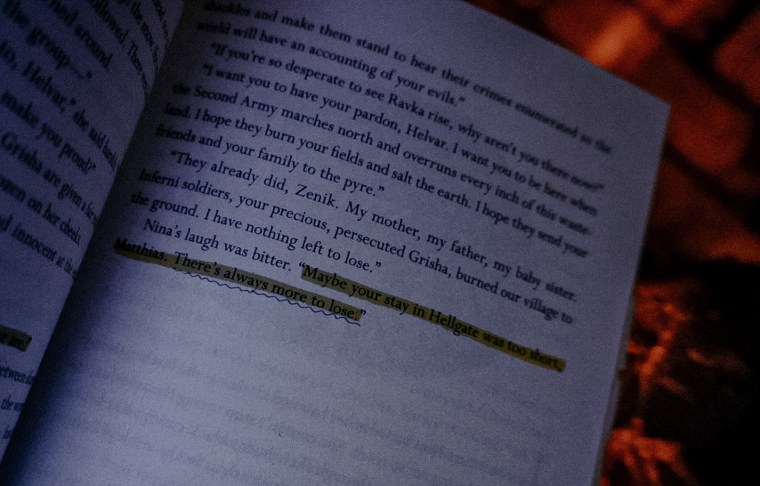

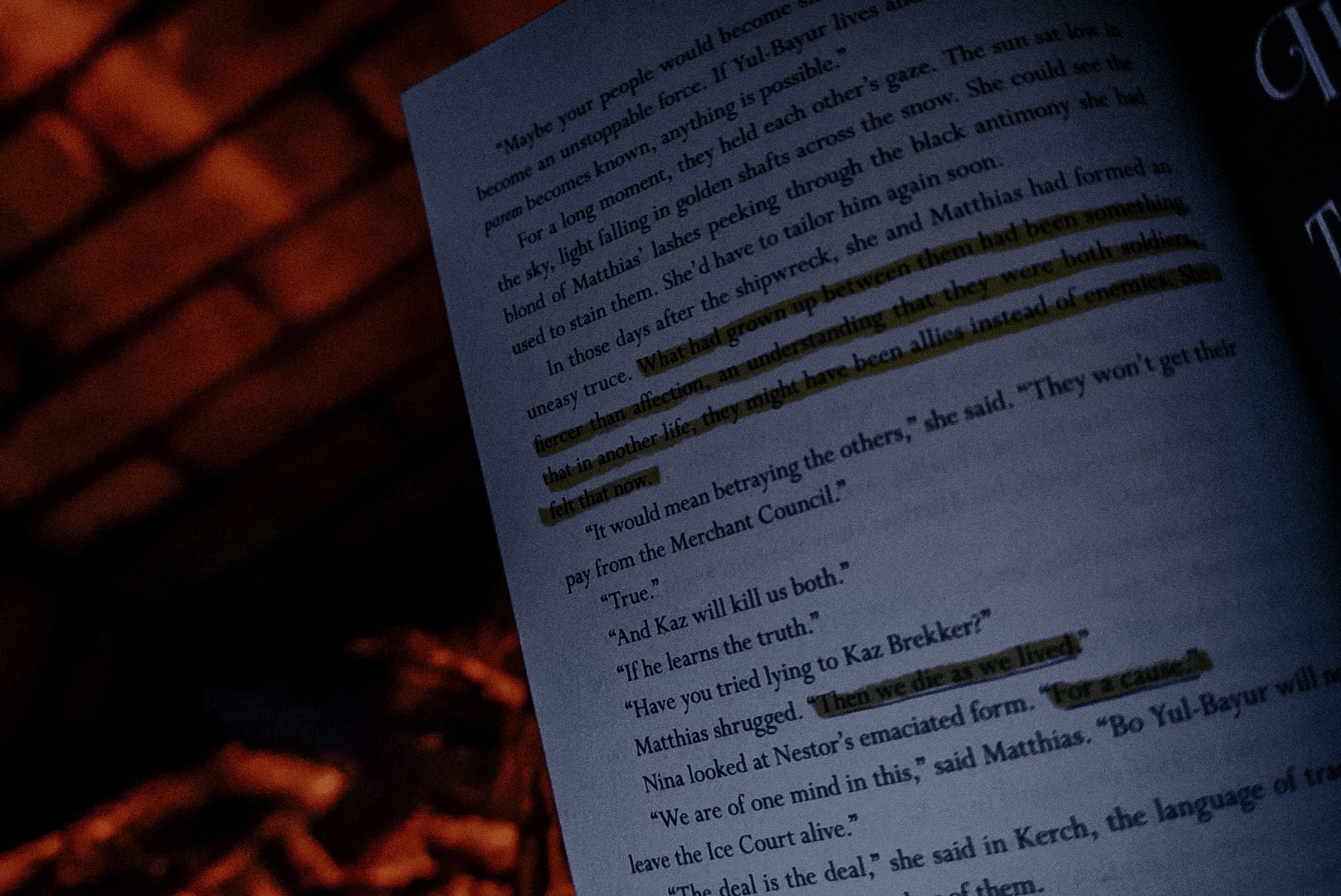

I loved so much about this novel. Inej’s character development was top tier, the creation of Kaz’s infamous legacy was exquisite, Nina and Matthias’ banter made my heart shatter and melt at the same time, and Wylan and Jesper found ways to make me cackle even in the heat of life and death situations.

However, where Six of Crows falters is in the world building. Bardugo doesn’t do enough to establish the magical elements or the lore of this world.

I found myself confused and disengaged, which removed me from the story until halfway through the book. While I’m willing to recognize my own fault of reading this duology prior to the Shadow and Bone trilogy, I still found it lacking and disappointing for Bardugo to not do this new story the justice of properly laying the foundation of how this world works.

I’ll give Six of Crows 4 Dirtyhands out of 5.

Leave a comment