Analyzing The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller

Hey guys, welcome back!

I’m not going to lie, it feels a bit weird to be writing a non-Shadowhunters analysis, but I’m also really excited to dig into a fresh topic as I start making my way through my never-ending TBR-piles and lists.

First up is The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller.

The Song of Achilles is a loose-retelling of Homer’s Iliad but told from the first-person perspective of Patroclus as he’s exiled from his father’s kingdom as a child and sent to Phthia, where he meets Achilles. Through Patroclus’ eyes, readers are taken through the journey of the two boys’ blossoming relationship as they grow up alongside each other and head to war together in an effort to seal Achilles’ legacy as “the best of all the Greeks.”

I heard enough about this book that I was prepared to have my heart broken, but I thought the ending would be what did the most damage. While the ending did make me emotional, the entire book was a 24/7 feels trip that I didn’t have a permission form for. However, it wasn’t as perfect of a story as I anticipated. I have some spicy takes.

Here’s the good, the bad and the best from The Song of Achilles.

The Good

There was a lot that I enjoyed about this book, so much that I could probably include everything in “the best” category. But, I made some hard decisions and decided some things were clearly better than others.

First, I think Miller’s choice to have Patroclus be the first-person narrator was perfect. Patroclus is a fairly minor part of the Iliad, so it was interesting to get a better look into who he is as a character and see Achilles through his eyes — because, let’s face it, Achilles can be a very unlikeable guy.

Through Patroclus, readers get to see a softer side of Achilles — the musicality, the kindness, the innocence, the humor and the humanity that is lost in the original tale.

It’s a really important part of Miller’s story, as well, because it establishes the stark differences between the two boys and how their opposite upbringings affected their relationship from the very beginning.

Patroclus’ backstory is really what just destroyed me.

Even from such a young age, he feels he’s a disappointment to his father, which is highlighted when their kingdom hosts the Olympic Games and five-year-old Achilles wins the youngest age division while Patroclus holds the victory laurels.

“That is what a son should be,” Menoetius tells Patroclus as they watch King Peleus dote over Achilles.

That one scene builds the notion that Achilles is everything Patroclus is not, and exemplifies the physical and emotional abuse Menoetius inflicted on his son and how it defined the boy. Patroclus is hyper-aware of his standing as a disappointment in the eyes of his father and the kingdom he rules, which is further highlighted when he is exiled by his father for accidentally killing Clysonymus.

“But my father was a practical man. My weight in gold was less than the expense of the lavish funeral my death would have demanded.” (18)

It builds Patroclus’ own characterization of himself, and sets the stage for his initial resentment toward Achilles and his surprise that the other prince would care enough about him to both warn him about the possibility of punishment and ask King Peleus for the exile to be his companion.

Achilles tells his father that he wishes to have Patroclus as a companion because, “He is surprising.”

Because Patroclus was so angry at Achilles when he arrived at Phthia, the young demigod took a liking to him. While the other exiled boys performed for the attention of Achilles, Patroclus treated him as just another kid — a prince just like him. They gave each other a sense of equality that neither had experienced prior.

The two boys have more in common than it seems: both were born to kings out of unfair and horrific circumstances and bore heavy expectations — but Achilles seemingly rose to his, where Patroclus failed. Then again, Achilles was given every advantage to succeed, even a direct blessing and prophecy from the gods.

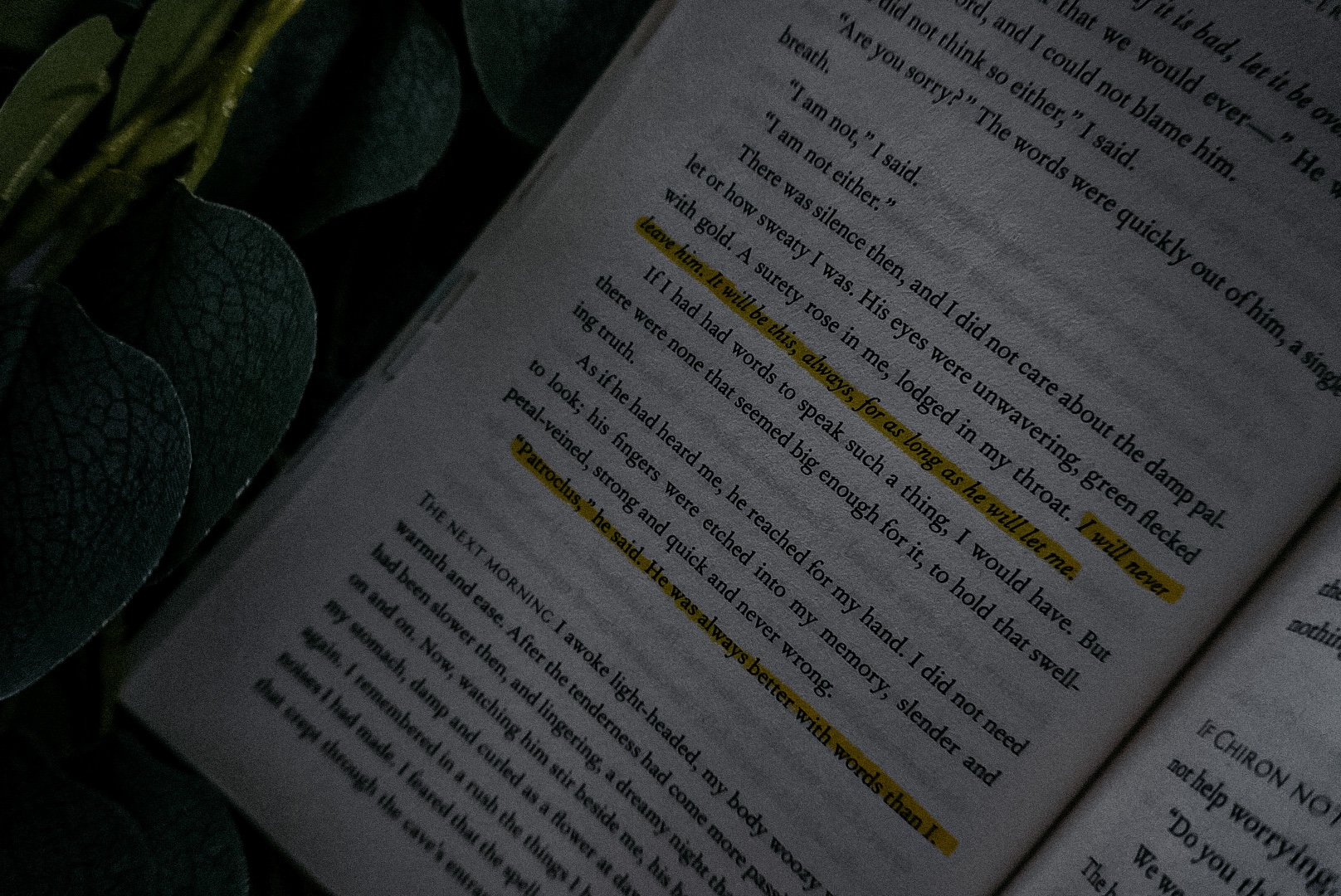

This first half of the book where Patroclus and Achilles slowly build their friendship, which develops into a romantic relationship, is such an incredible journey.

The Song of Achilles is an extremely slow-paced novel, which I usually despise, but Miller did it exceptionally well. She used the unhurried tempo to really capture the spirit of these two characters and pull readers into their relationship. It gives readers time to truly become attached to Achilles and Patroclus in a way the Iliad never did — because Achilles was a jagoff and Patroclus barely mentioned.

The pacing and Patroclus’ raw and honest perspective allows for character development. Brilliant character development.

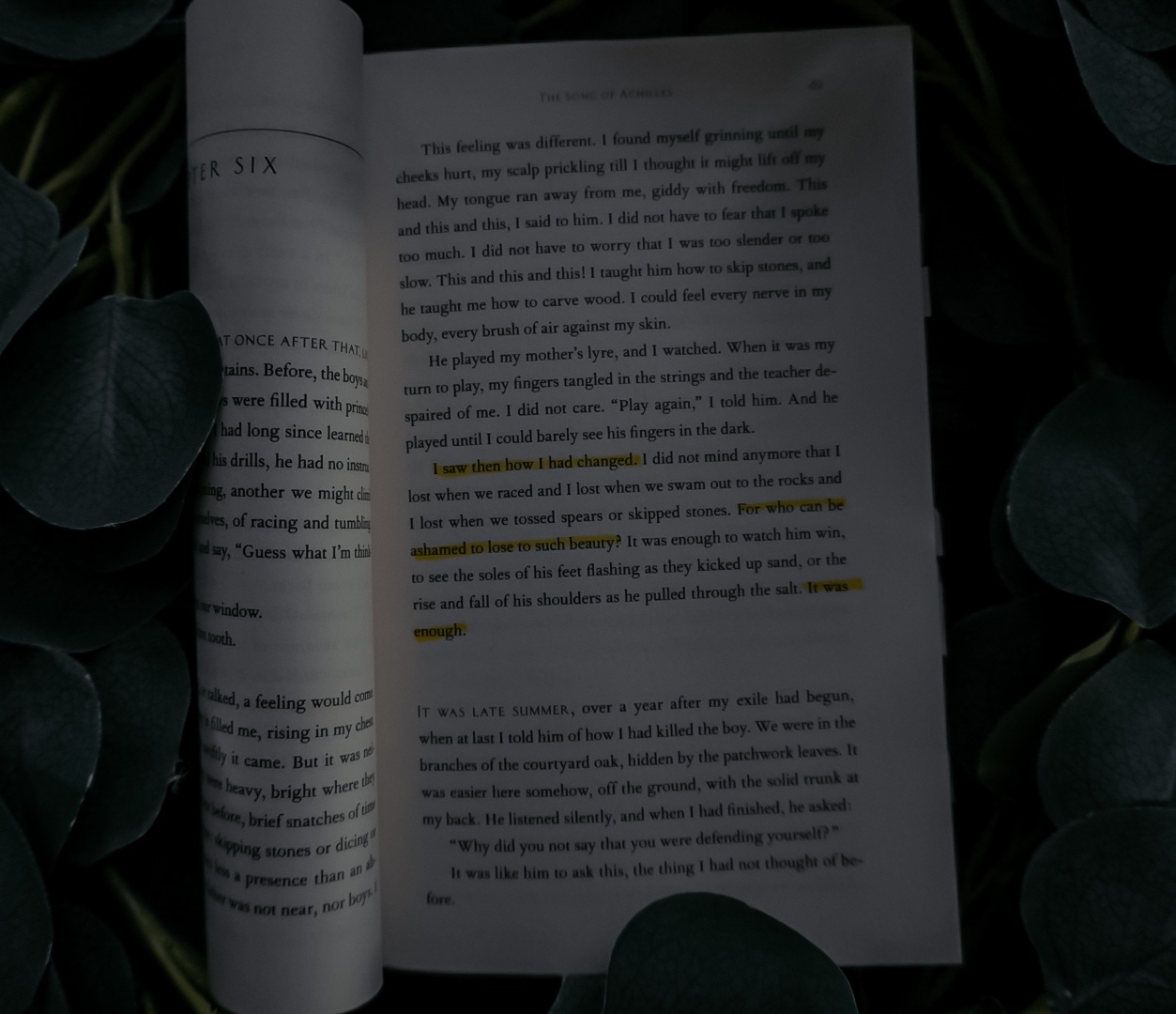

We start with very stripped down innocence — of Achilles and Patroclus juggling figs together in their shared room and of Patroclus watching Achilles play his mother’s lyre. Both figs and the lyre are constant reminders throughout the story of the innocence their relationship was built upon.

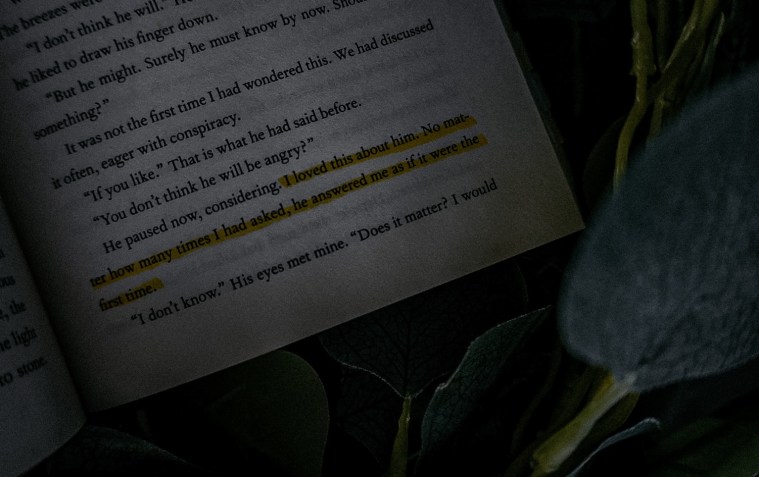

But there’s also a boiled down trust. They are honest with each other when no one else is. Achilles is the first person so ask Patroclus why he didn’t lie or defend himself when accused of killing the boy back in his home kingdom, giving our narrator the realization that he was not exiled for murder, it was “a lack of cunning”.

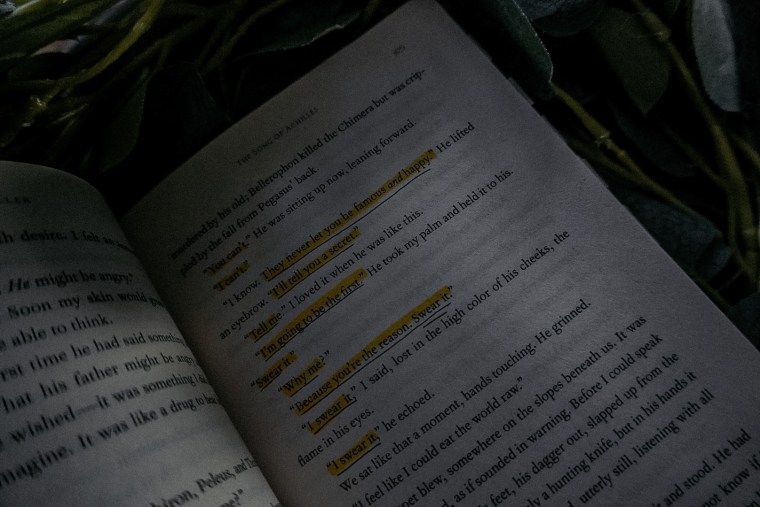

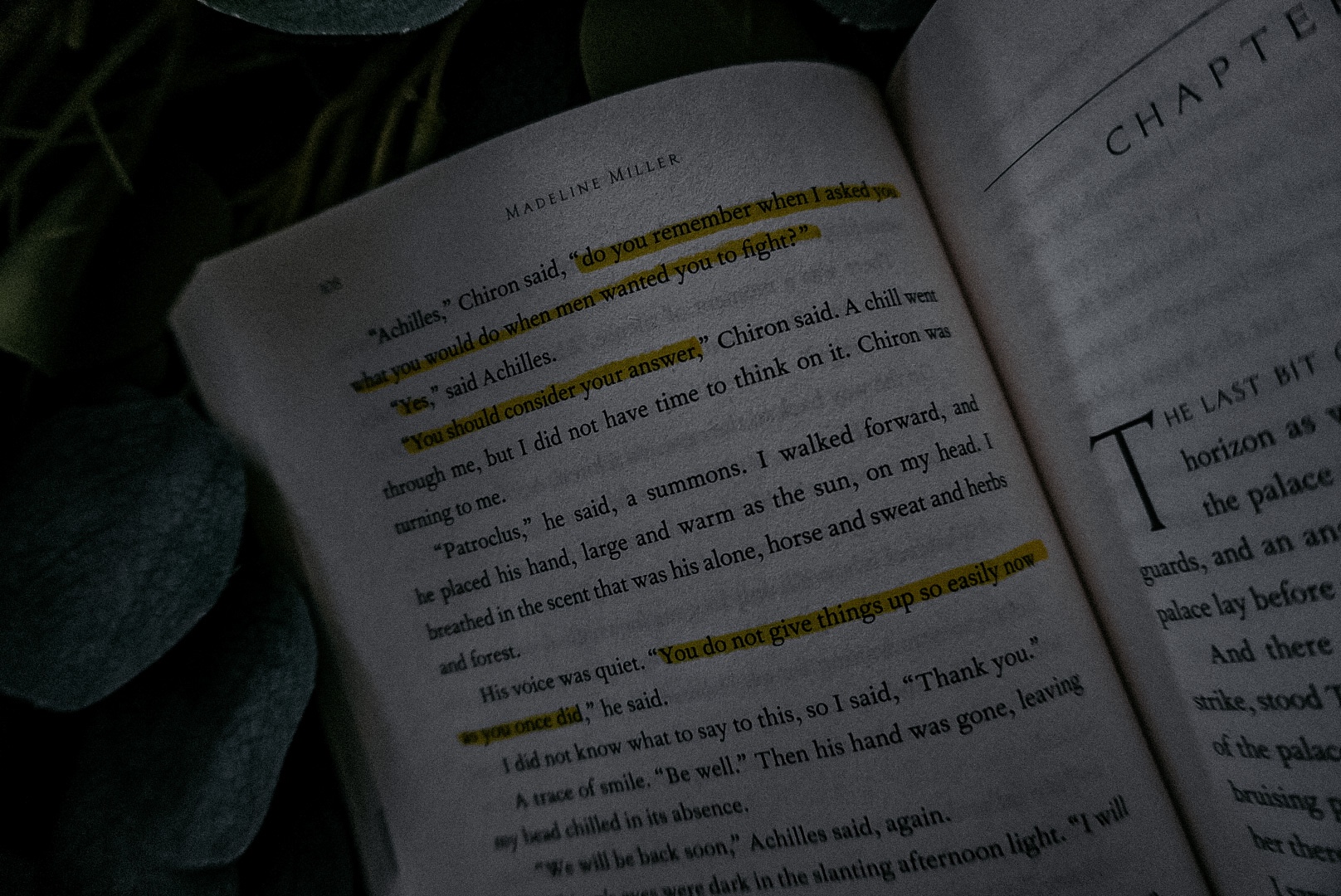

Then, when Achilles asks Patroclus to “name one hero who was happy,” Patroclus is honest in saying he can’t and swears to help Achilles become the first. He never tries to ignore or cover up the fact Achilles was born to be a hero and heroes meet tragic ends.

Their time with Chiron takes Achilles and Patroclus’ childhood innocence and starts to mold it into maturity. They are no longer just Princes, they are capable and competent in ways other boys of their status are not. They are not even boys anymore, they are young men. This change is marked by their friendship turning into intimacy during this time period, which begins with Patroclus giving Achilles figs on his birthday (symbolism, baby!).

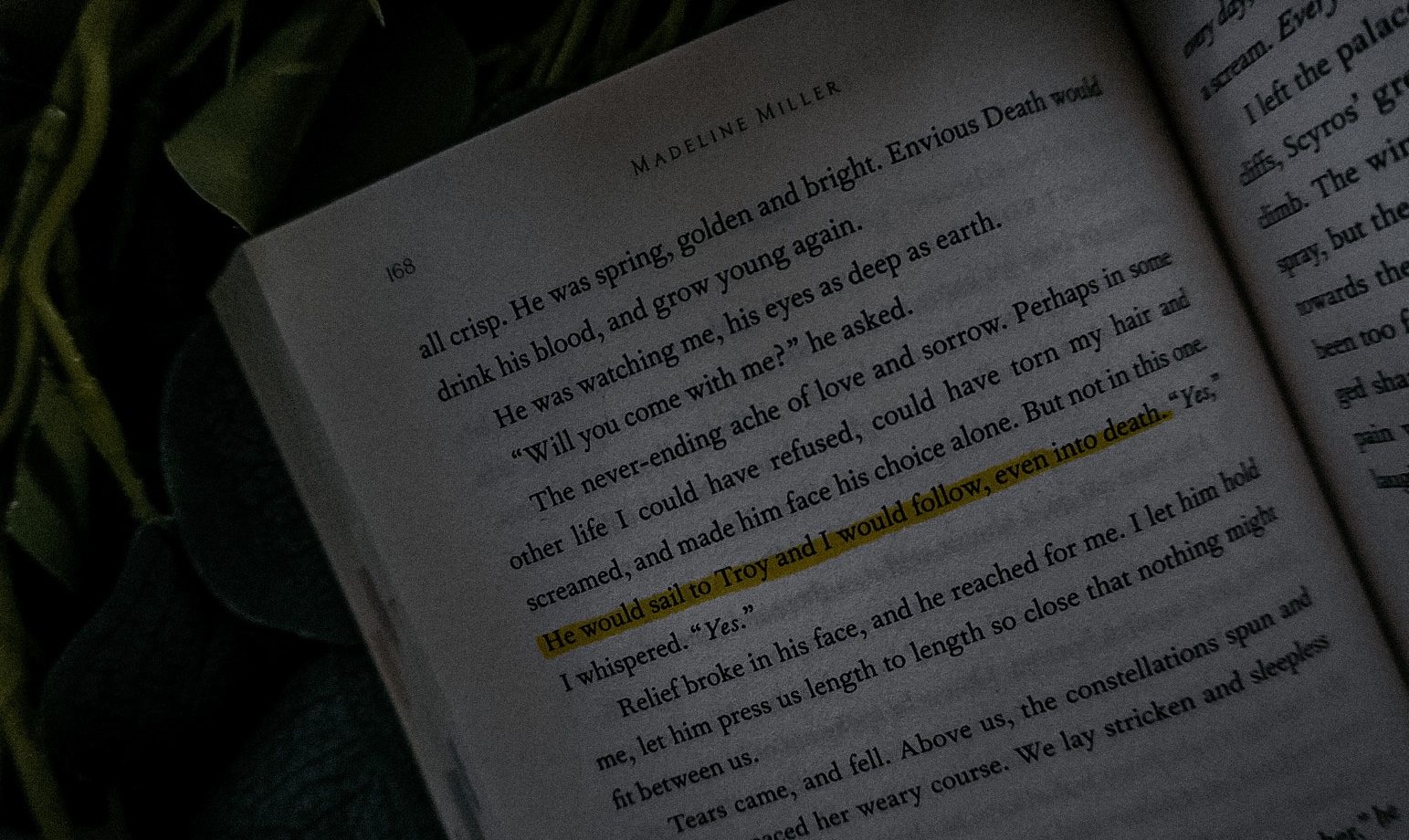

Then as war calls, the last bits of innocence are torn away.

Thetis sends Achilles to Scyros to hide, where his mother pressures him into having sex with the princess so Deidameia would bear a child in exchange for her giving Patroclus his location. Of course Thetis lied to her son for her own selfish wants, which leads to this thought by Patroclus:

“He had always trusted too easily; he had so little in his life to fear or suspect. … His trust was a part of him, as much as his hands or his miraculous feet. And despite my hurt, I would not wish to see it gone, to see him as uneasy and fearful as the rest of us.” (135)

This is S-tier character development, in my opinion.

This passage shows how Patroclus feels comfortable enough to question Achilles, even if it’s just to himself, while also depicting how Patroclus is an asset to the demigod as more than just moral support. Patroclus has experience with a life that doesn’t hand you everything on a silver platter, making him more intune to the way the world and its people can twist and manipulate you without care or concern — which comes into play later on when the Trojans are at the gates to the Greek camp.

This tenderness Achilles has is called out by Odysseus after the murder of Iphigenia under the disguise of a wedding.

“You will help him leave this soft heart behind. He’s going to Troy to kill men, not rescue them. He is a weapon, a killer. … You can use a spear as a walking stick, but that will not change its nature.” (207)

This is a major turning point for the two boys. Patroclus becomes more assertive, while Achilles becomes colder. Six pages after Patroclus’ conversation with Odysseus, Achilles sheds the first drops of blood in the Trojan War.

But Achilles still holds onto some of that kindness, mostly because of Patroclus, who is often sickened by what the other young man must do during war. He goes along with Patroclus’ plan to save women and girls given away as war prizes by claiming them as his own, and when raiding Cilicia, Achilles allows one of Eetion’s sons to live so that the bloodline didn’t die.

Meanwhile, Patroclus built his own reputation as a successful medic — becoming a favorite among the Greek camps for his gentleness and care.

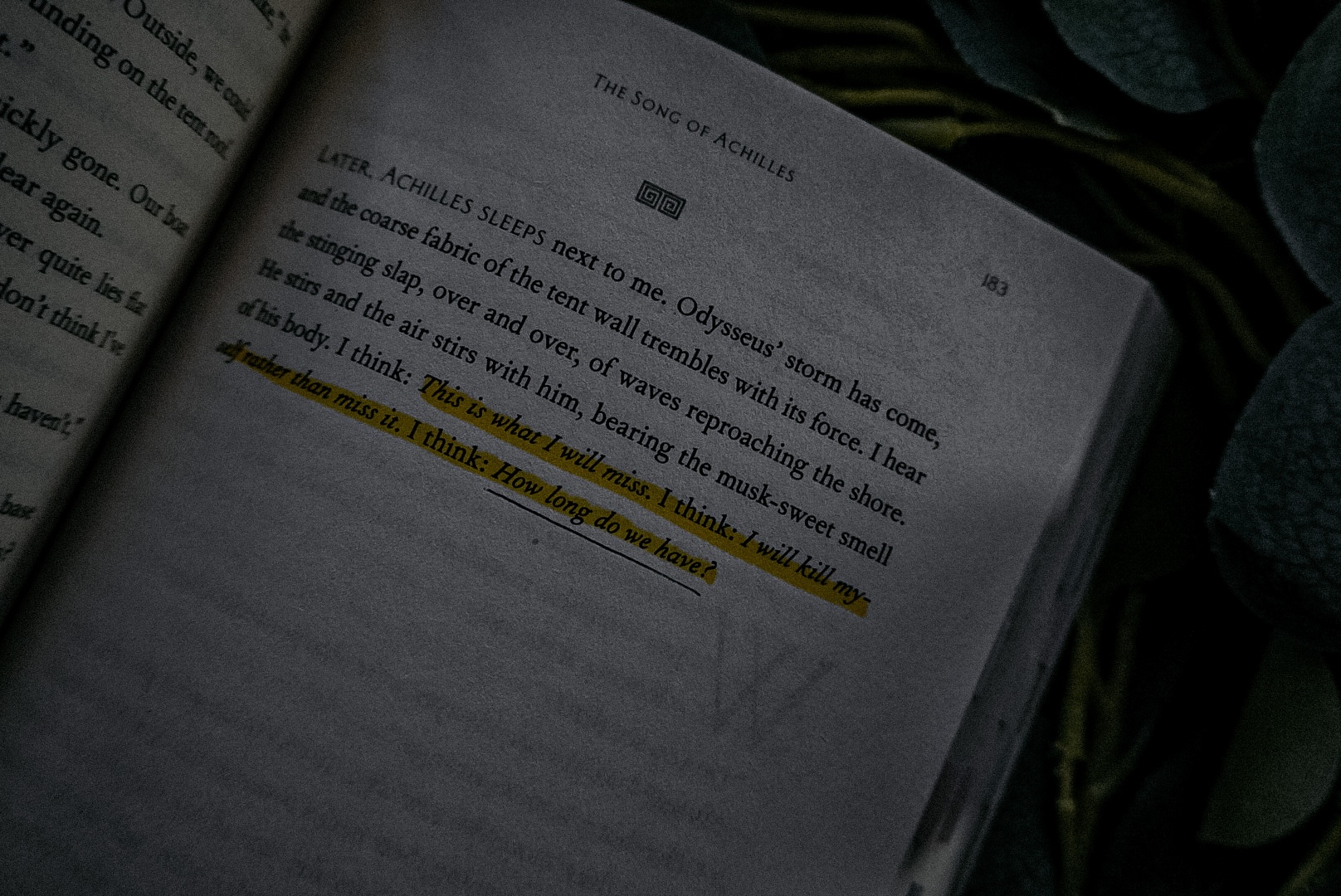

However, as war and the thirst for glory saturates Achilles’ personality, he loses the pieces of himself that Patroclus fell in love with. The men Patroclus had befriended and made his own legacy among, are dying because the man he loves became too proud and infatuated with a legacy that is slipping through his fingers unknowingly, which brings me to … the bad.

The Bad

This feels like a spicy take, but I wasn’t as wounded by the deaths of Patroclus and Achilles as I thought I would be. Of course, I knew they were coming, and I knew by whom and how. But it was more than just prior knowledge of the legend of Achilles.

After 334 pages of buildup, both Patroclus and Achilles die within the span of 18 pages. It felt rushed and empty compared to the sweet, steadiness of the lead up to when Apollo unmasks Patroclus disguised as Achilles, allowing Hector to make the final blow.

At first, I didn’t even realize Patroclus was dead, because he’s still the narrator. It’s not clarified until 10 pages later that his spirit isn’t at peace because rituals weren’t performed. I was very lost for a few minutes.

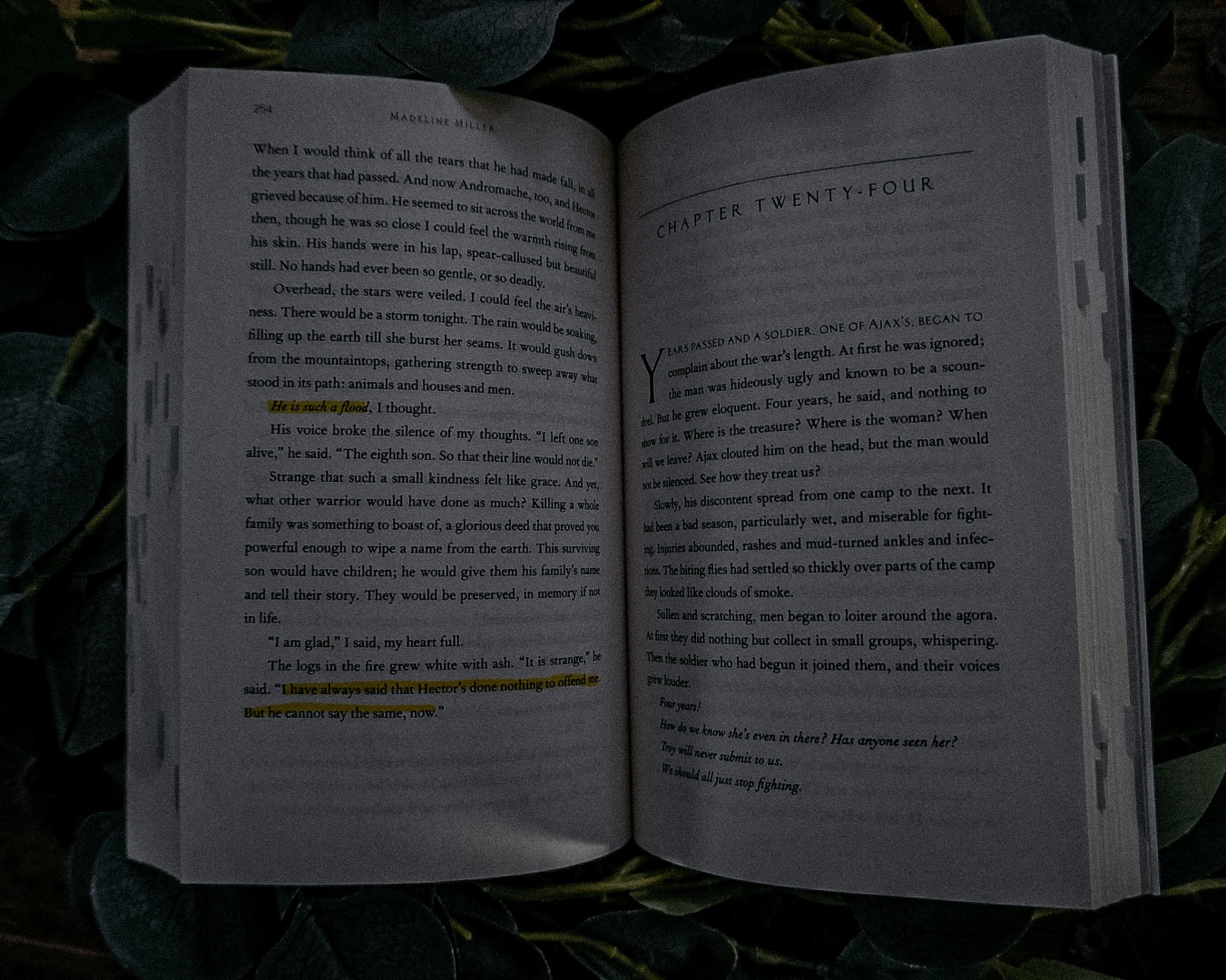

It follows the source material by showing Achilles’ pitfall into grief — his victory over Hector, the cruelty of dragging the prince of Troy’s body behind his chariot for days, the ultimate choice to prepare the body and give it over to the family, etc.

Eighteen pages was just an awkward amount of time for me.

I was hoping Miller would stray from the original to give readers Patroclus’ romanticized vision of suicide after Achilles’ murder. Who doesn’t love a little Romeo and Juliet action? A quicker death for both would’ve been more tragic and impactful — a direct hit, rather than chasing down death out of rage and grief.

I’m going to talk about the themes of legacy and honor under “the best” category, but it felt like a hollow ending for Achilles with no real conclusion for his character development. He remains all the things Patroclus despised — proud and irrational and cruel. Sure, he gives Hector’s body back, but he is still a ruthless murderer, and that’s what he’s remembered for due to his own pride that tarnished his reputation.

The best word for this section of the book, which is essentially the novel’s climax, is unsatisfying.

I wanted something a little more heavy and hard-hitting, rather than an easily missed, but also too predictably made allegory for the frailty of humanity and length of life.

There’s also 16 pages between Achilles’ death and the end of the book, which is equally an awkward amount that felt too rushed for me to really grasp the totality of it.

A decade-plus long war is won by Achilles’ punk ass son, Neoptolemus, who is only 12 years old and an absolute dick. There’s no other way to put it. This kid is a dick. Because he was raised by Thetis, he lacks the humanity that made Achilles likable in this story, and it gave the boy the same disdain for humanity that Thetis despised in her own son. He is more god-like than human, and, thus, has a lack of empathy even for his own father.

Which brings me to something else that was just plain awful — the weird rivalry between Thetis and Patroclus. We never really get a full explanation on why Thetis was so terrible to Patroclus. The theory I picked up on was that she hated Patroclus because he kept Achilles tied to Pythia and grounded in humanity, and less willing to seek immortality alongside her.

Or perhaps she thought Patroclus made Achilles soft? Patroclus was always the other boys’ moral compass and sense of self. Or — or maybe Thetis was worried that Patroclus would hurt Achilles as Peleus hurt her?

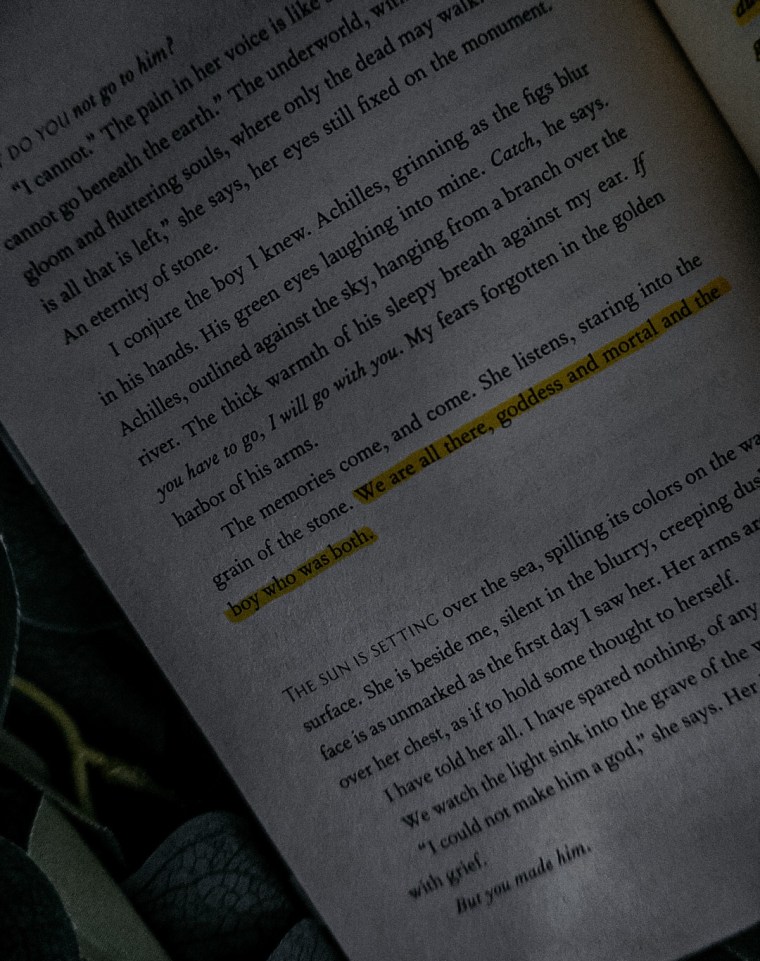

It’s never clarified, but Thetis realizes she made some bad parenting mistakes in the final pages of the novel as she listens to Patroclus tell the memories he has of Achilles — in her defense, she was made a parent out of tragedy, which is awful in its own horrific way.

It was just a weird side-plot that was never truly addressed, but was still somehow resolved in the final scene when Thetis scratches Patroclus’ name into Achilles’ tomb so that their souls can reunite in the underworld.

Problems have solutions, so I would say the easy fixes for my gripes would be to make everything after Achilles’ murder an epilogue and to shorten the space between their deaths — whether that be by cutting up some of the grieving done by characters or by reworking the story to make Achilles’ death come faster.

The epilogue solution would make the ending feel more complete, to me. It wraps up the love story between Patroclus and Achilles before entering Pyrrhus’ own plotline to end the war and complete Patroclus’ characterization.

As for the Thetis situation, I would say to either make it a more prominent and relevant part of the story or drop it entirely. I know the saying is usually to show instead of tell, but it was just too loose of an interpretation with such little basis that it was frustrating, especially to end with it.

Also, final grumbles from me, why did Miller just completely ignore the curse — AKA Achilles’ Heel? In the Iliad, Paris kills Achilles by shooting him in the heel, the only spot left unprotected by the demigod’s dip in the River Styx. But in The Song of Achilles, we only get a single line by Paris when he asks Apollo where to shoot him because he heard he was invulnerable. But then, Paris’ arrow goes through Achilles’ heart to kill him. Why?

WHY?

(The “why” is probably because it makes Achilles more human not to be invulnerable, which is why Apollo tells Paris, “He is a man. Not a god. Shoot him and he will die.” Perhaps Miller thought it was more tragic for Achilles to be shot in the heart because it would be symbolic of the heartbreak he feels for Patroclus’ death? No matter what the reason, I wasn’t a fan.)

The Best

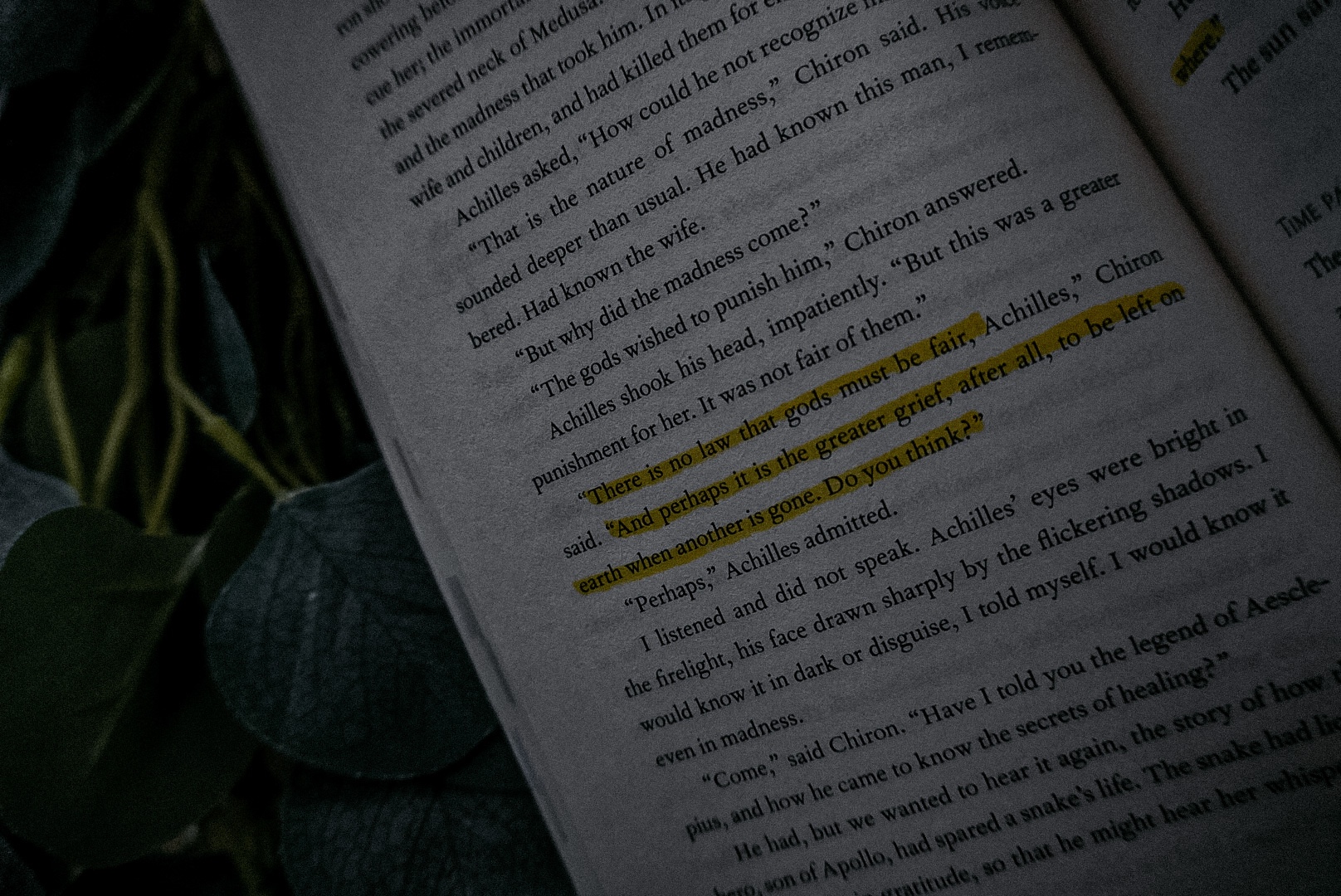

This might be an odd thing to consider “the best”, but I just really, really, really loved how the themes of legacy and honor and fate played out in The Song of Achilles, especially during the downfall of Achilles.

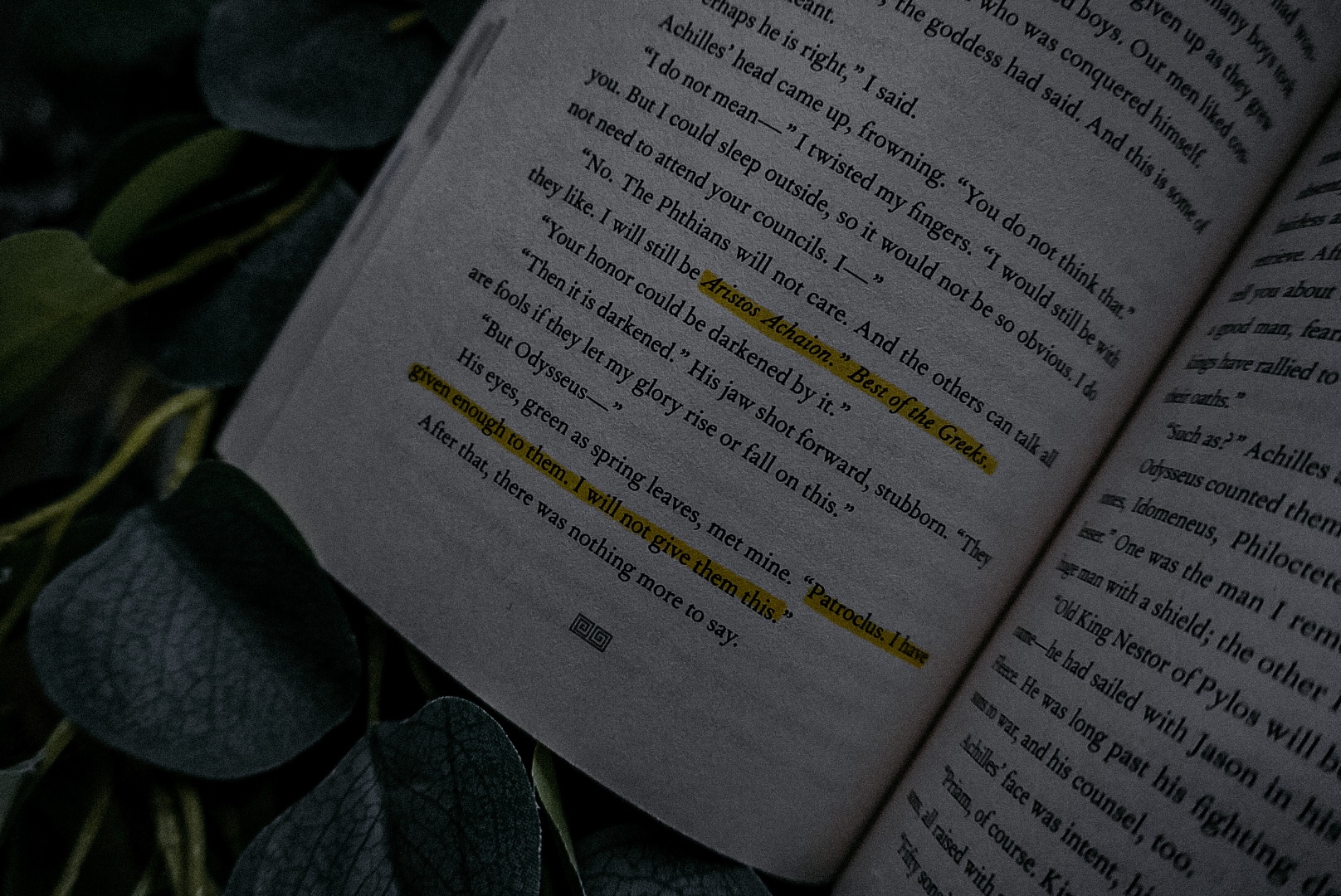

Achilles is born from a prophecy given to Peleus that his son will be “Aristos Achaion”. Because of that, the young demigod grows up with the expectation of greatness tied to his self worth. It’s something that is always on his mind even as a child.

“Do you want to be a god?”

“Not yet. … I’d like to be a hero, though. I think I could do it. If the prophecy is true. If there’s a war.” (56)

In a way, Achilles’ life does not belong to him. It belongs to the Fates, who have curated his existence as part of an elaborate scheme in the Trojan War. The Fates have bound Achilles to a life of tragedy that he can only try to outrun but never escape.

Thetis brings Deidameia to Achilles’ room to lay because of a prophecy that their son will be the victor of the war. The war lasts over a decade because of a prophecy that Achilles’ death will come after that of Hector’s — allowing Achilles to lengthen his life by letting the other man live. Patroclus’ death is foretold by a prophecy given to Thetis that, “the best of the Myrmidons will die before two more years have passed.”

Achilles’ entire life was spent chasing some prophecies and avoiding others, until they all came crashing down.

It was incredibly clever to use prophecy as foreshadowing that not only gave hints to the future but also became an integral thread in the fabric of Achilles’ character. He is consumed by prophecy, which ends up being his downfall.

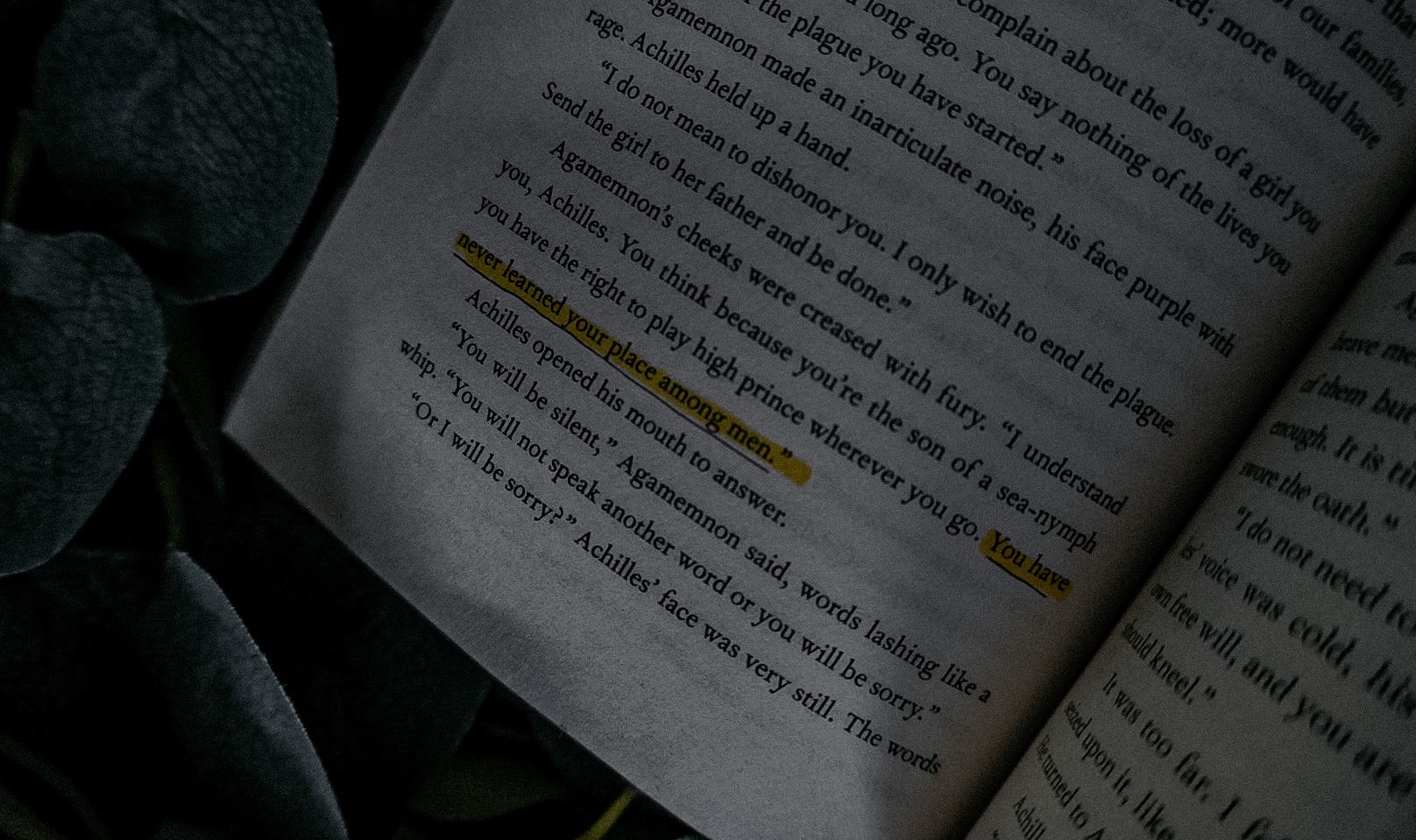

As the war raged on, the kings and princes around Achilles started tearing away the last shred of his humanity. For the first time, he is being challenged. It starts with an honest gesture of calling out Agamemnon for keeping the young priestess and causing the plague. Achilles is only trying to save the Greeks, but honesty is not always met with reward, especially in war.

“Without me, your army will fall. … I will watch it and laugh. You will come, crying for mercy, but I will give none.” (283)

Agamemnon then threatens Achilles’ honor by demanding Briseis be reclaimed, and he cracks under his own hubris — because all he’s ever had was Patroclus and the prophecy that promised him a short life on earth but a long one in memories.

“My life is my reputation. It is all I have. I will not live much longer. Memory is all I can hope for.” (295)

This is Achilles’ undoing. The princes have finally pulled him into their personal war that stems from greed and envy as they fight for honor and respect while losing both.

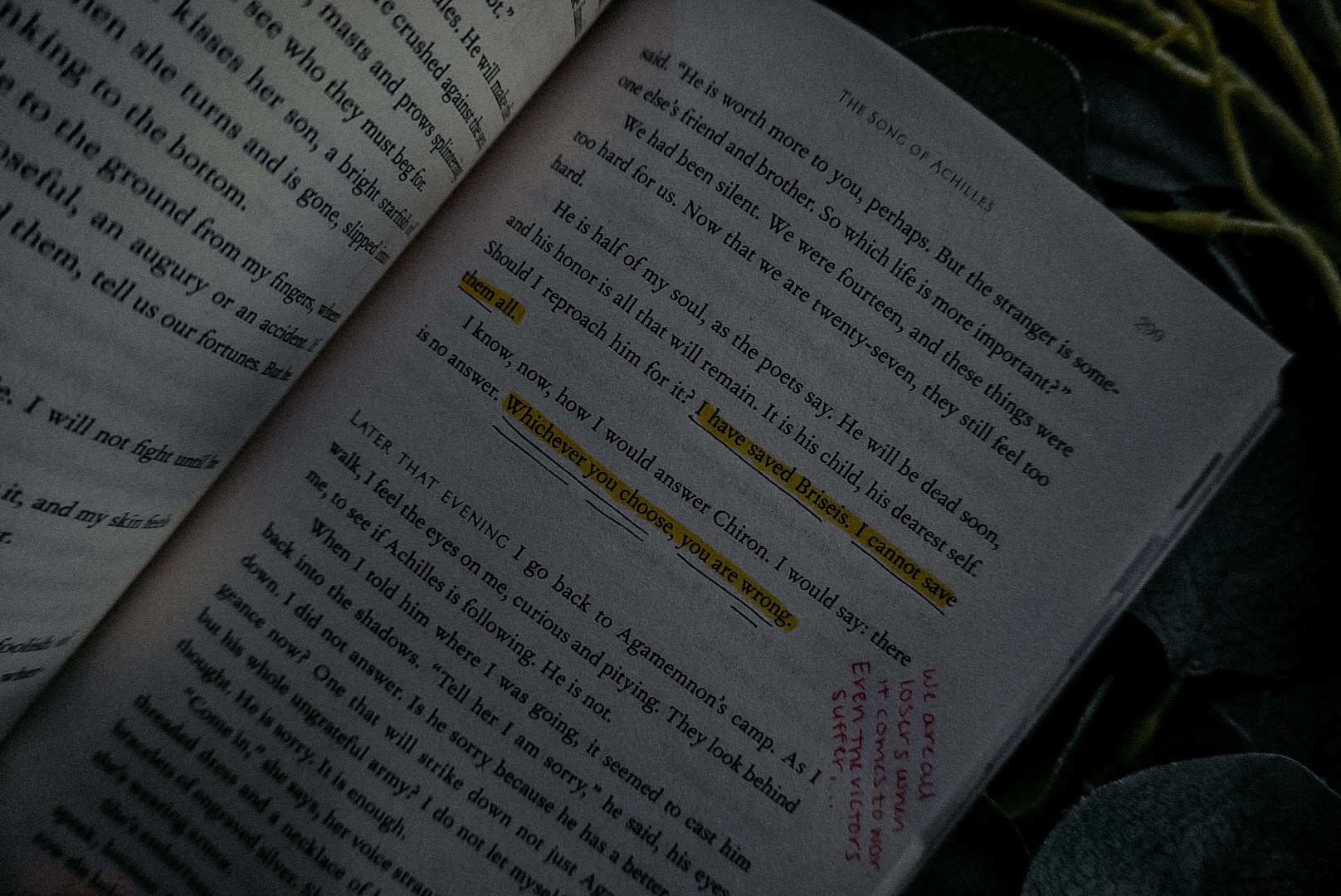

“He is lost in Agamemnon and Odysseus’ wily double meanings, their lies and games of power. They have confounded him, tied him to a stake and baited him. … I would untie him if I could. If he would let me.” (315)

Achilles refuses to fight in the Trojan War any longer. He allows for his own men to die because of his selfishness. The Greeks learn to despise him. His legacy is destroyed by nobody but himself. But in Achilles’ undoing, Patroclus steps up.

He won’t allow for his lover’s legacy to be put at a detriment as he becomes someone he’s not.

Through everything, Patroclus still sees Achilles as the intrinsically good boy he met so long ago — somebody worthy of the title of Aristos Achaion. But as Achilles fastens his armor to Patroclus, it’s clear that the best of the Greeks is the man ready to die not for honor or pride or legacy, but for love.

And that man does die without the honor he deserves because it was not bestowed upon him by the gods. He didn’t fight for the gods and their glory as Achilles did, he fought for the men that believed in him and that he believed in.

For all the goodness and honor he put into the world, Patroclus is the one whose soul is not at peace at the end of the Trojan War despite Odysseus even urging Neoptolemus to allow them to put Patroclus’ name on Achilles’ tomb — with a little persistence from Patroclus’ spirit — which is immediately shot down.

“In my father’s armor. With my father’s fame. He has none of his own.”

“True. But fame is a strange thing. Some men gain glory after they die, while others fade. What is admired in one generation is abhorred in another.” (363)

I LOVED the message portrayed in this sequence of actions. It’s just — sigh — perfection. It was the only redeeming quality of the ending, in my opinion. In the fight for legacy, Achilles and Odysseus and Agamemnon are the victors, but they are memorialized by their cruelty and wrath. Patroclus may not be as prominent of a figure in Greek mythology, but he remained true to himself and died protecting what he loved.

Even in death, he fights for Achilles’ legacy to be more than just the vengeful man he became in grief. Achilles’ life should not be measured by the lives he took, but the life he lived, which is such a great way to wrap up Patroclus’ character arc, as well. He’s much more confident and less afraid to speak up, but he also remains compassionate and kind as he speaks to Thetis of the wrongs done to Achilles.

“But how is there glory in taking a life? We die so easily. Would you make him another Pyrrhus? Let the stories of him be something more.” (366)

The Fates predicted Achilles to be Aristos Achaion, but it was Patroclus who was the best of the Greeks.

Side note! In the Iliad, Patroclus is actually a fairly competent fighter. He’s not as helpless as he appears in The Song of Achilles. But, I liked the change in character, because it allowed for more contrast between the two men and made Patroclus’ decision to pose as Achilles more powerful. By having Patroclus gain respect among the soldiers by being a medic and caring, it sent a more impactful message of how spilling blood is not the only way to create a legacy.

Final review

The Song of Achilles is so much more than a loose retelling of the Iliad. It’s a tragic love story rooted in childhood innocence and honesty that developed into trust and intimacy as Patroclus and Achilles grew up alongside each other.

As much as I wanted it to be, this was not the perfect novel I expected it to be based on the hype.

I adored Patroclus as a narrator that both gave more context to an otherwise minor character and made Achilles much more likable than the original text. I thought the building of the two characters’ relationship was flawlessly and beautifully executed as they repeatedly evaded the tragic prophecies given by the Fates. And the themes melted seamlessly into the character development of our main protagonists as war brought out the best in Patroclus and the worst in Achilles.

It’s more than a retelling and it’s more than a love story, it’s a cautionary tale of the fruitless conquest of war, how honor and pride can strip away at your very essence and the difference between earning your own legacy and being handed one. The Song of Achilles is a reminder of mortality and the separation between the gods and humanity.

However, the unhurried pacing that establishes such a strong connection between the readers and the relationship of Patroclus and Achilles is tossed aside for an awkwardly rushed climax way too late in the book that makes the ending feel unsatisfactory.

In an attempt to portray an allegory for love and life, Miller diminishes the excellent work she’d done to build her novel into something worthy of perfection.

The Song of Achilles still felt oddly unique despite its categorization of being a retelling. It had a fresh perspective, an interesting angle on a classic, a simplistic writing style that was engaging and characters I absolutely fell in love with.

Miller just tried to do too much with too little.

It was a fabulous read, and I’m excited to eventually get to her other novel Circe. But I feel a little disappointed that I can’t properly give out the five-star rating I expected before starting the novel.

The Song of Achilles gets 3.2 figs out of 5.

Leave a comment